Until the Mushroom Artist Sprouted

Shigeo Otake

2022

Extraordinary creatures frequently appear in my work. Some have wings adorned with eyes, others have faces covered by anemone-like tentacles. Akin to monsters or mythical creatures, they are seamlessly woven into the lives of everyday people. My artistic aim has been to blur the boundary between the mundane and the fantastical, painting a realm where the ordinary and the otherworldly coexist. Initially inspired by insects and marine life, these creatures, over time, have given way to the emergence of mushrooms in my paintings.

Amanita Club, 2014. Tempera and oil on board. 40.9×31.8cm

My first meaningful encounter with mushrooms happened in 1985, about three years after my inaugural solo exhibition in Tokyo. I had been living in an aged storefront in the western quarter of Kyoto City, which I shared with a friend as both a home and a studio. Despite its ramshackle condition, the storefront was nestled in a neighborhood bordered by a wooded cemetery and a shrine surrounded by ancient trees.

One day, near a thicket of bamboo alongside a local road, I stumbled upon a mushroom of considerable stature. Standing at forty centimeters, it was a revelation. Never had I imagined that mushrooms could achieve such a size, nor that they would sprout so near to where I lived. Curious, I borrowed a field guide to mushrooms from the library and identified it as Macrolepiota procera, the Parasol mushroom, a common, edible fungus. As my knowledge of mushrooms grew, they began revealing themselves to me during my strolls through the neighborhood.

First encounter with Macrolepiota procera (Parasol Mushroom), near Kyoto studio in 1985.

Because the field guide focused on culinary mushrooms, I soon began sampling those that were unmistakably non-toxic. Local spots like H Park and M Shrine were abundant with edible varieties such as the Lactarius hatsudake, Boletus edulis, and Russula virescens, though without a single trace of the prized Tricholoma matsutake (matsutake). These places became veritable classrooms for my study of mycology, immersing me more deeply in the fungal kingdom. Although mushrooms increasingly claimed a significant place in my life, they did not immediately find their way into my paintings. Typically associated with Japanese “Kawaii” culture, the quintessential mushroom form—cap and stem—initially did little to stir my artistic impulses.

Years after my initial foray into the world of fungi, I made an unusual discovery at M Shrine: a caterpillar with what appeared to be a short stick protruding from it. I instantly thought of cordyceps, a genus of parasitic fungi that grows from the dead bodies of insects or spiders. I was familiar with these mushrooms from children’s science books and comics, but had never seen one firsthand. I had presumed that these fungi only grew in the wilderness, yet here was one right in front of me. Once again, I delved into research at the library and found Cordyceps Fungi Illustrations, published by Hoikusha Books. The book depicted over one hundred fifty types of cordyceps, forms so bizarre that they surpassed the furthest reaches of my imagination and thoroughly captivated me. Throughout history, humanity has been drawn to fictitious hybrid creatures like the winged horse Pegasus from Greek mythology, mermaids, or the Japanese Nue, a chimera with a monkey’s head, a tiger’s legs, the body of a raccoon dog, and a snake’s tail. Real-life hybrids of insects and fungi, however, are a discovery of a different order. With hundreds of Cordyceps species to be found throughout Japan, some in surprisingly populated areas, my quest for them expanded exponentially. I broadened my searches, cycling to distant shrines and temples and cataloging nearly twenty types.

Purpureocillium atypicolum

(a spider-associated entomopathogenic fungus)

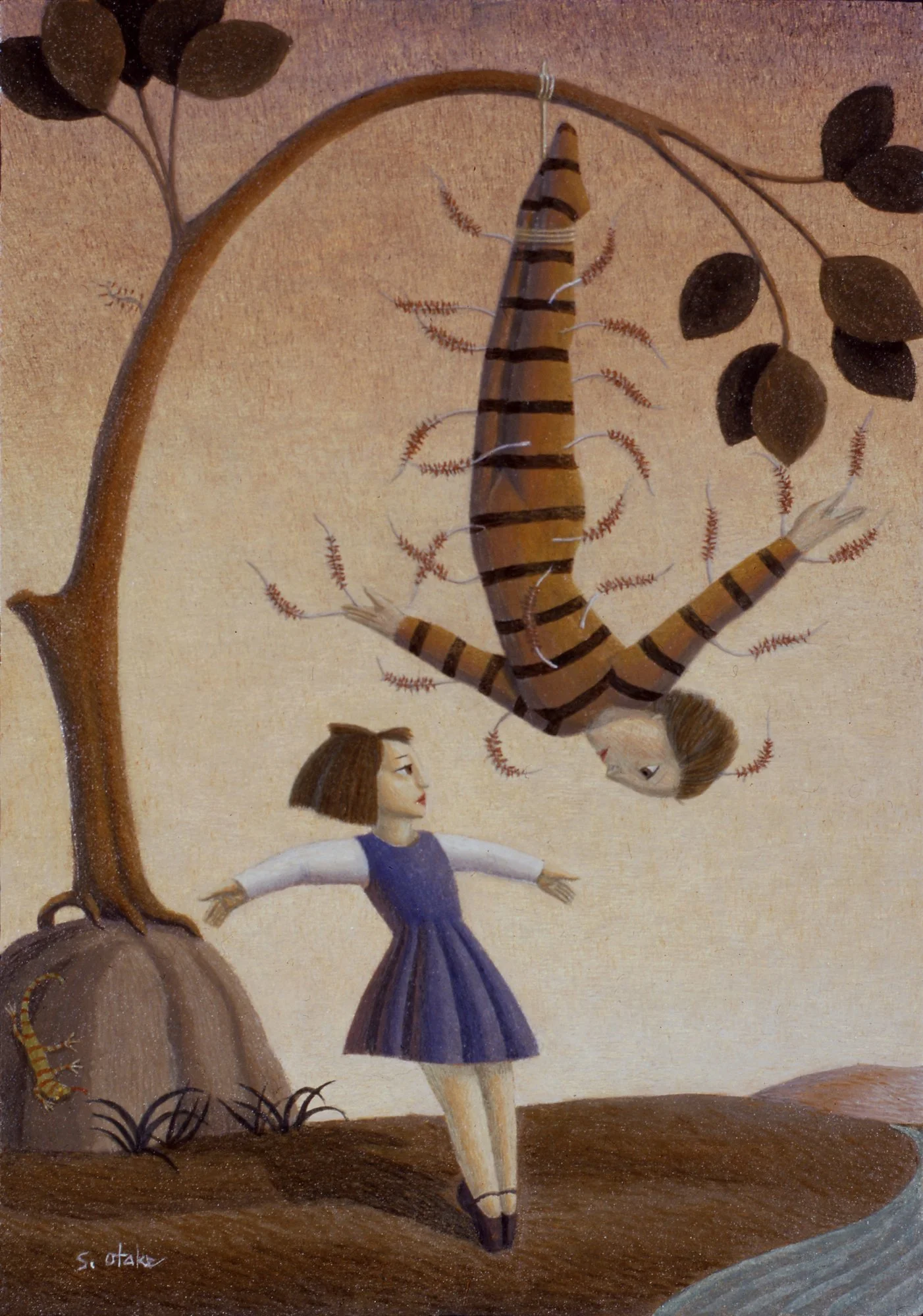

As I grew more acquainted with these fungi, I became eager to integrate their intriguing forms and fascinating life cycles into my art. I naturally thought of them emanating from human bodies, but depicting corpses was unappealing to me. Instead, I painted people wearing cordyceps costumes, a concept that I developed into the series “Cordyceps Masquerade.” The diversity of the species, each with its own unique morphology and ecology, continuously inspired my creative process.

Cordyceps Masquerade, 1997. Tempera and oil on board. 116.7×90.9cm

During that time, sightings of Ophiocordyceps sobolifera, Purpureocillium atypicola, Cordyceps annullata, and others were common in Kyoto’s urban temples and parks. However, toward the late 1990s, these sites underwent frequent renovations, and the number of cordyceps dwindled. My fervor cooled. A decade after my first discovery at M Shrine, my collection included fewer than thirty types.

One spring, a season during which I typically wouldn’t venture out, I went to the mountains on a whim and, on another impulse, descended to the riverbank. To my delight, I discovered the long-admired Ophiocordyceps odonatae and the extremely rare Yosiokobayasia kusanagiensis. Once I realized that such uncommon species were nearby, they became more visible to me. My passion for cordyceps was reignited. I wore rubber boots and searched the riverbeds and the undersides of leaves on riverbanks, collecting twice the number of species as I had before, including several rare varieties. My favorite, which I discovered hanging from a tree branch over a river, produced numerous thick, centipede-leg-like mushrooms from the segments of a bagworm.

The Man of Ophiocordyceps jinggangshanensis, 1999. Tempera and oil on board. 15.8×22.7cm

Ophiocordyceps jinggangshanensis

Ophiocordyceps jinggangshanensis is an aerial species that grows in large numbers on the body segments of geometrid moth larvae. The fruiting bodies are needle-like, measuring 5 to 7 mm in length and 0.5 to 0.7 mm in diameter. They are dull-pointed, with a pale yellowish-gray stipe and a light brown fertile area near the middle. It appears from July to August on tree branches in deciduous forests and is considered rare.

Various atypical mushroom forms also began appearing in my works. First was the Phallus indusiatus, the Veiled Lady mushroom, which I came across in great numbers in bamboo forests nearby. In the mornings during the rainy season, bicycling along the forest pathways, I would suddenly encounter a foul smell. Following this scent, I would come upon an elegant Veiled Lady, which emits a fecal odor to attract insects for spore dispersal. The irregularly net-patterned capped Morel was first discovered in spring before other mushrooms appeared at M Shrine. This mysteriously shaped mushroom would later frequently feature in my works. My interest had shifted from consuming them to admiring their forms.

Queen of Mushrooms, 1991. Tempera and oil on board. 19.1×33.4cm.

As my mushroom-themed artworks increased, a Traveling Fungi Garden appeared in the city square one day. Visitors unknowingly inhaled spores and became infected. The fair soon departed, leaving behind a devastated city and a people transformed by mushrooms. Like the Cordyceps infestation, the incessantly sprouting mushrooms were intractable and, despite intensive treatments, the people eventually turned into immobile sculptures, marking the end of human civilization. The residual collective consciousness of the people gradually merged with the fungi to form a cross-species consciousness. After various trials and tribulations, the fungi chose to coexist with humans, leading to the birth of a fungal-human species, the development of a fungal civilization, and the dawn of the Mycocene. There are countless others, such as the “Mushroom Tarot” series.

Arrival of the Traveling Fungi Fair, 1991.Tempera and oil on board. 19.1×33.4cm

The Mycocene: The End of the Beginning, 2004. Tempera and oil on board. 40.9×24.2cm

As my output of mushroom art grew, so did my circle of acquaintances related to mushrooms. I began attending gatherings of mushroom enthusiasts, exchanging information, and increasingly identifying as a mushroom artist. A few years ago, I returned to my hometown of Kobe. Although my physical strength had declined, limiting my excursions, I conducted my explorations as usual. It seemed to me that the mushrooms that appeared in my paintings were proliferating more vigorously than ever.