The Cordyceps Masquerader

Shigeo Otake

2022

A Curious "Plant"

In 1723, a Jesuit missionary named Father Parennin brought back a strange specimen from China to his native France. It looked like a caterpillar with a thin, plant-like stalk sprouting from its head. The people of China, observing how it seemed to be an insect in winter and a plant in summer, called it dong chong xia cao, or "winter insect, summer grass."

A few years later, in 1726, the French scholar Réaumur examined this mysterious being and presented his findings at the Academy of Sciences. His report is considered the first written record of what we now know as Cordyceps. At the time, Réaumur thought it was a caterpillar attached to the root of a plant, but that turned out not to be the case. Further study revealed its true identity. What looked like a plant was in fact a fungus that had parasitized the larva of a moth, with the slender stalk being its fruiting body. In other words, it was a mushroom growing out of an insect.

Ophiocordyceps sinensis (Dong Chong Xia Cao)

Encountering Cordyceps

I first learned that somewhere in the world there existed a strange organism called Cordyceps, a mushroom that grows out of an insect, when I was still in elementary school. It appeared in a ninja manga by Sanpei Shirato, featured in a children's magazine. In the story, a young boy sets out on a journey to find a miraculous herb called Niku-shiba, a relative of Cordyceps, in hopes of saving his sick mother. Eventually, the boy himself becomes a Cordyceps. The final scene, where a ninja uncovers a massive Cordyceps specimen in a snowfield and finds the boy lying beneath it as if in peaceful sleep, has stayed with me ever since.

For many years afterward, Cordyceps faded from my thoughts. After graduating from university, I became a painter and shared an old storefront with a friend, turning it into a combined living space and studio. Though modest and weathered, the house was surrounded by abundant nature, an ancient burial mound covered in foliage, and a nearby shrine nestled among giant trees.

As I wandered the area, I started noticing mushrooms more often, which led me to buy a field guide on fungi. Although I didn’t find any matsutake, there were plenty of edible varieties like Lactarius hatsudake, Boletus edulis, and Morchella species. I was captivated. Soon, I found myself venturing farther by bicycle, deep into the hills, in search of new fungi.

First encounter with Macrolepiota procera (Parasol Mushroom), near Kyoto studio in 1985.

One day, while exploring the forest behind a temple, I came across something I'd never seen before. From the clay-rich soil protruded a coral-like form, about 1.5 centimeters in diameter, with a fleshy color. It had to be a fungus, though I couldn’t place it. Acting on a sudden hunch, I carefully dug around it with a twig. To my amazement, a tiny cicada larva appeared, it was my first encounter with Ophiocordyceps sobolifera, known in Japan as semidake. The fungus was still immature and hadn’t yet developed its signature long fruiting body, so I hadn’t recognized it at first.

Not long after, I also came across Purpureocillium atypicolum (kumotake) and Ophiocordyceps annullata (himekuchikitanpotake). I had always imagined that Cordyceps grew only in remote mountain valleys, far from human habitation. I was stunned to find them so close to home. I immediately dove into research at the library and came across a book titled Fungal Atlas of Cordyceps. It was a revelation.

The book’s author, Mr. Shimizu, had illustrated more than 150 species of Cordyceps in exquisite detail. Their forms were so grotesquely beautiful, so beyond the reach of human imagination, that I felt utterly overwhelmed. Throughout history, people have been drawn to mythic creatures, hybrids like Pegasus, the Chimera, mermaids, and Japan’s own nue. Yet here were real-life beings that seemed to fuse insect and fungus. And dozens of them were living right here in Japan.

The book explained that many of these Cordyceps species were considered common and could be found surprisingly close to human settlements. That was enough to make me forget all about ordinary mushrooms. I threw myself into the search for Cordyceps. In my very first year, I managed to find nearly twenty different species.

Ophiocordyceps annullata

Defining the Term

At this point, I feel it is necessary to clarify the term “Cordyceps” because its usage varies depending on the person. In its original and narrowest sense, “Cordyceps” refers to the organism that Father Parennin brought back from China. This species, now known as Ophiocordyceps sinensis (formerly Cordyceps sinensis), grows in the high mountains of China and Nepal, at elevations between 3,000 and 4,000 meters. It parasitizes the larvae of ghost moths, a group distinct from the ghost moths found in Japan, and is highly valued as a rare and potent traditional medicine. Parennin first encountered it at the Qing imperial court.

The vague impressions I once held of Cordyceps as something extremely rare and found only in remote mountain valleys most likely came from this particular species, Ophiocordyceps sinensis. It appears that the name “dong chong xia cao” entered Japan through Nagasaki along with the medicinal use of the fungus. Unfortunately, this species does not grow naturally in Japan.

However, Japan has many fungi that parasitize insects and spiders, such as Ophiocordyceps sobolifera (semidake) and Cordyceps militaris (hachitake). Over time, the term “Cordyceps” came to be used more broadly to refer to any fungus that grows out of insects. In China, “dong chong xia cao” is used exclusively for Ophiocordyceps sinensis, while other insect-parasitizing fungi are referred to as chong cao, which means “insect grass.”

Morphology of Cordyceps. The specimen illustrated is identified as Cordyceps sp., and is considered conspecific with, or closely allied to, Cordyceps ninchukispora.

In other words, there is both a narrow and a broad definition of Cordyceps. To avoid confusion, some people describe the broader group as “Cordyceps-like fungi” or “Cordyceps relatives,” or they adopt the Chinese terms chongcao or chongcao fungi. Personally, I often use the term chongcao because it is short and convenient, though not yet widely familiar. In this writing, I will use “Cordyceps” in the broader sense. My focus is not on Cordyceps as a medicinal substance, but on the fungi that grow from insects in the forests and hills near my home. When I need to refer to the original Cordyceps specifically, I will either use its scientific name or call it “sinensis Cordyceps.”

Broadly speaking, Cordyceps are fungi that grow from insects. More precisely, they infect and kill insects or spiders and then use the nutrients from the host’s body to form fruiting structures. Fungi such as Laboulbenia, which attach to insects but do not kill them, are not included. Similarly, fungi like Beauveria, which are often called entomopathogenic molds, do kill their hosts but do not form distinct fruiting bodies. These are not considered Cordyceps, even though they have been identified as the anamorphic, or asexual, forms of Cordyceps-group fungi.

Spider Sisiter (Unica), 2009. Tempera and oil on board. 243 × 334 mm

When people think of mushrooms, they often imagine the classic shape with a cap and a stalk. These belong to a group called the Basidiomycetes. Cordyceps, on the other hand, belong to the Ascomycetes. Their fruiting bodies take forms such as cups, rods, or thin threads, which look very different from typical mushrooms.

Cordyceps fungi are part of the Clavicipitaceae family within the order Hypocreales. This broader group includes closely related genera such as Torrubiella and Shimizuomyces. These are generally considered part of the Cordyceps family. Some people believe that only fungi in the genus Cordyceps, which is also called the “Cordyceps genus” in Japanese, should be given the name. However, species in Torrubiella are nearly identical in structure, differing mainly in that they lack a long stalk. Shimizuomyces parasitizes the fruit of plants rather than insects, which places it outside the literal definition of fungi that grow from insects, but it closely resembles Cordyceps in form.

Even within the genus Cordyceps, there are species like Tampotake and Hanayasuritake that parasitize underground fungi such as Elaphomyces instead of insects. Technically, these too fall outside the definition, but many people still consider them part of the Cordyceps group.

In recent years, developments in molecular phylogenetics, which reconstruct evolutionary relationships based on DNA data, have significantly altered how we classify living organisms. Cordyceps fungi are no exception. What was once the single genus Cordyceps has been reorganized into three families and four genera within the Hypocreales order. These include Cordyceps in the Cordycipitaceae family, Metacordyceps in the Clavicipitaceae, and both Elaphocordyceps and Ophiocordyceps in the Ophiocordycipitaceae.

To keep things straightforward, I will refer to all of these as part of the broad Cordyceps group.

Purpureocillium atypicolum

Species and Ecology

Just how many types of Cordyceps are there? The answer depends on how broadly we define the group, so it is difficult to give a precise figure. Based only on those with formal scientific names, there are about 550 species, including around 380 that fall under the broad classification of Cordyceps.

Some of these species have different names for their sexual stage, known as the teleomorph, and their asexual stage, known as the anamorph. Since this would result in duplication, the anamorphs are not included in the count. There are also cases where the same species has been described more than once under different names, so the true number may need to be slightly adjusted.

Conversely, there are many species that have not yet been formally named, and new ones continue to be discovered. If we take those into account, the total could easily reach between 600 and 700. In Japan alone, more than 300 species have been recorded, which makes the country something of a stronghold for Cordyceps diversity.

My fieldwork is focused on the outskirts of Kyoto. Although this area is not especially known for Cordyceps, I have already found close to a hundred species in their sexual form alone. That means one-sixth of the world’s known Cordyceps and about one-third of the Japanese species have been found just in this area. I would say that makes it quite an exceptional field.

We still do not fully understand how Cordyceps attach themselves to insects. The mechanism likely varies between species. It might seem that these fungi grow from insect corpses, but that is not the case. Once an insect dies, there is no time for fungal spores to take hold, as ants and other scavengers arrive almost immediately and carry the body away. The fungus must therefore infect a living host.

Its spores or germinated hyphae lie in wait on the forest floor or beneath leaves. When an insect brushes past, the fungal matter adheres to its surface and penetrates the skin, beginning the infection. The host continues to move about while carrying the fungus, but once the fungus has spread enough inside the body, the insect succumbs.

Curiously, ants do not seem to touch these infected bodies. As the fungus spreads within, it eventually fills the entire insect with white mycelium. When the time is right, the fruiting body breaks through the surface.

Some species emerge fairly soon after infection, but for most, the life cycle spans a full year. They infect and kill their hosts in summer or autumn, then remain dormant through the winter. It is only in spring that the mushroom appears and releases spores. Depending on the region, the time just after the rainy season is usually when Cordyceps are most abundant.

The Mycocene, The Beginning of the End, 2004. Tempera and oil on board. 409 × 243 mm

Where the Cordyceps Live

Although I have already written that Cordyceps are not limited to remote, mountainous regions, there are more extreme examples. For instance, Osamushitake has been found in public parks right in the heart of Tokyo. As for Kumotake, it seems entirely possible that it appears in nearly every park in Tokyo during the rainy season.

Given that they are so prevalent, you might think they would be easy to find. However, there are good reasons why they are not. First of all, they are small. Most species are no more than two or three centimeters tall, and many are under five millimeters. One might think that anything growing out of an insect would be obvious, but the insects are usually buried underground or hidden inside rotting wood. Even species in the epigeal group, those whose host bodies are exposed, tend to grow on the underside of leaves, making them hard to notice.

Finding them requires some knowledge and experience. You start by reading the terrain, the types of trees, and how moist the ground is in order to narrow down the likely areas. Forests around old temples or shrines, especially those with long histories, are excellent places to search. These areas often yield cicada-related species such as Ophiocordyceps sobolifera or Kiasioosemitake. Kumotake is also common there. Slopes along mountain trails are another good spot where you may find Pupatake, Hachitake, and Kame-mushitake. If you come across decaying fallen trees in such places, it is always worth examining them. You might find species associated with beetle larvae, such as Himekuchikitanpotake or Kuchikimushitsubutake. Maruminoaritake also grows in rotting wood.

Once you identify a promising location, you should lower your gaze to within a few dozen centimeters of the ground and observe it carefully, scanning slowly and closely. Look among fallen leaves, tree roots, and moss for anything that seems slightly out of place. If something catches your eye, inspect it with a magnifying lens. If you see tiny grain-like structures arranged on its surface, there is a good chance it is a Cordyceps species.

Some epigeal species also grow on trees or grasses along streamside slopes. You often find Gayadorinagamitsubutake or spider-associated fungi from the genus Torrubiella in such areas. By wearing rubber boots and stepping into the stream, you can lift and inspect leaves of riverside plants one by one. Finding Yanmatake or Shakutorimushiharisenbon would make the effort truly worthwhile.

Places where the same species of Cordyceps reliably appears each year in the same season are called “tsubo.” Spores are dispersed in these sites every year, and the fungal presence in the soil is constant. These places also provide a suitable habitat for the insect hosts, so even though many are killed by the fungus, they do not disappear completely.

If you find a spot that feels similar to a known tsubo, it is worth investigating. Once you find a good location, remember it and revisit in a different season. You might encounter other species that emerge at different times of year. As you accumulate more knowledge and experience in this way, you will eventually reach the point where no matter when you go out, you can count on encountering several kinds of Cordyceps.

The Pleasure of Cordyceps

Although no one has ever said it to my face, I am sure many people secretly wonder, "What could be so interesting about looking for something like that?"

If I had to name the first thing that draws me to Cordyceps, it would be their extraordinary forms. The insect’s body is preserved just as it was in life, while a vivid fungal stroma bursts through it. This strange combination of beauty and decay is striking. Each species, and indeed each individual specimen, has its own complex morphology. There is a haunting elegance in seeing a fungus, which is essentially a reproductive organ, emerging from a dead body. The strangeness, even the eeriness, is part of its allure.

Another source of fascination lies in the search itself. Cordyceps are hard to find. Many species are rare. There is so much still unknown that every trip into the field offers the possibility of discovery. You do not need to go deep into the jungle. Sometimes, even near your own neighborhood, you might find a candidate for a new species or one of the incredibly rare types that have only been collected a handful of times.

In short, I would describe it as a kind of easy-access treasure hunt. In terms of rarity, Ophiocordyceps sinensis is not rare at all. It is harvested in such volume that it is exported around the world.

For me, there is another kind of pleasure that comes from practical benefit. Cordyceps make compelling subjects for my paintings. When I come across a particularly rare or strikingly beautiful specimen, I feel compelled to express the feeling in a painting. Of course, simply painting a dead insect as it is would feel too harsh and lifeless. Instead, I imagine human figures wearing Cordyceps as a kind of costume. This became the concept for a series I call Cordyceps Masqueraders. I must have created several dozen of these works by now.

At exhibitions, when these paintings are on display, someone often points to the club-shaped form emerging from the head of a figure and asks, “What is that?” When I reply, “It’s a mushroom,” some people look puzzled, while others respond, “Oh, Cordyceps.” Surprisingly, many of them are not even mushroom enthusiasts. It seems that the word “Cordyceps” has become increasingly recognized in Japan.

In the West, however, it is still largely unknown. I once tried to explain my work in broken English to an American tourist at a solo exhibition, but it did not come across at all. It seemed that the very idea of a mushroom growing from an insect was unfamiliar. There are a few English terms for Cordyceps, such as “plant worm” or “vegetable wasp,” but I have never met a foreign visitor who actually knew them.

Cordyceps Masquerade, 2024. Tempera and oil on board. 320 x 410 mm

The Making of a Cordyceps Seeker

As I mentioned earlier, my encounter with Cordyceps came by chance. To wrap things up, I would like to quickly retrace my steps and share how my connection with these fungi deepened over time.

In my first year, I discovered nearly twenty species of Cordyceps. For a while, though, that number remained unchanged. The species I found were all common ones, the kind that could be spotted almost incidentally during an ordinary mushroom hunt. I only went out during the rainy season or in autumn, the seasons known for edible mushrooms. At the time, I had not yet learned the specific methods for finding Cordyceps, and I still believed that rare species could only be found deep in the mountains.

One spring, in a moment of impulse, I went out at a time I usually would not. Another whim led me down to a riverbank. There, I found something incredible. It was Kusanagihimetampotake, a species so rare it had only ever been recorded in the hot springs of Yamagata. The realization that such a rarity could emerge so close to home changed everything. It felt as if a veil had lifted, and suddenly I could see what I had never noticed before. The number of species I collected, stagnant for years, quickly doubled.

This time, the new finds included many unusual and rare types. Shakutorimushiharisenbon, Hayakawasemitake, Shuirokuchikitanpotake, names that still thrill me. My passion for Cordyceps, which had calmed for a time, reignited and only intensified.

I began joining communities of fellow enthusiasts and started sharing information. Eventually, I was venturing into the hills even in winter. I bought a digital camera capable of macro photography. I began using the internet and uploaded photos of the Cordyceps I found. Soon, I began receiving responses from mushikusaya, as Cordyceps lovers call themselves, from all across the country.

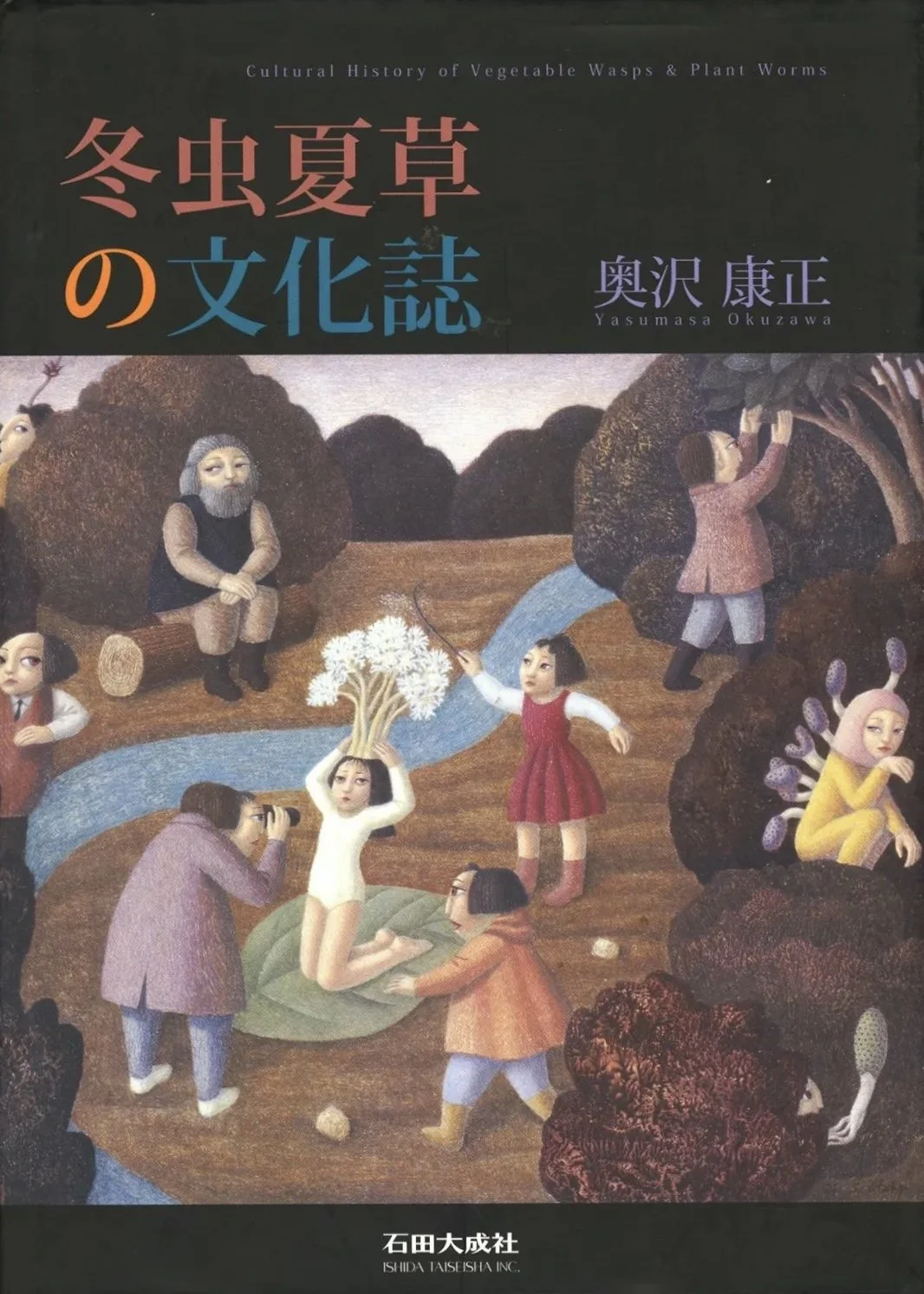

Published in 2012 as a self-funded project, Culture History of Vegetable Wasps & Plant Worms was edited by Yasumasa Okuzawa with contributions from Cordyceps experts, including Shigeo Otake, who also created the artwork for the book’s cover.

I invested in a high-quality microscope and started examining asci and spores. Thanks to that, I was finally able to identify even anamorphic fungi that I could not distinguish before. I launched a blog called Mushikusa Nisshi, where I shared images and notes from every outing.

The number of species I collected approached one hundred. Including the anamorphic forms, the total surpassed one hundred fifty. I began receiving messages from researchers in Japan and abroad who had come across my blog. I created more artworks based on Cordyceps, including a series called The Mycocene, in addition to Cordyceps Masqueraders. A television program even featured my artworks and specimens, and before I knew it, people began calling me a “Cordyceps Painter.”

At the same time, many of the familiar forests where I had often gone collecting were repeatedly redeveloped under the name of satoyama restoration. Some of my most treasured sites, the tsubo, have disappeared. Cordyceps no longer appear as abundantly as they once did. These days, I often find myself riding trains and buses to search for new fields, setting out once more in pursuit of that quiet, uncanny life-form hidden beneath the leaves.