Undefined Spectacle

Zhao Xiaodan (Curator)

2023

I. From Ending to Beginning

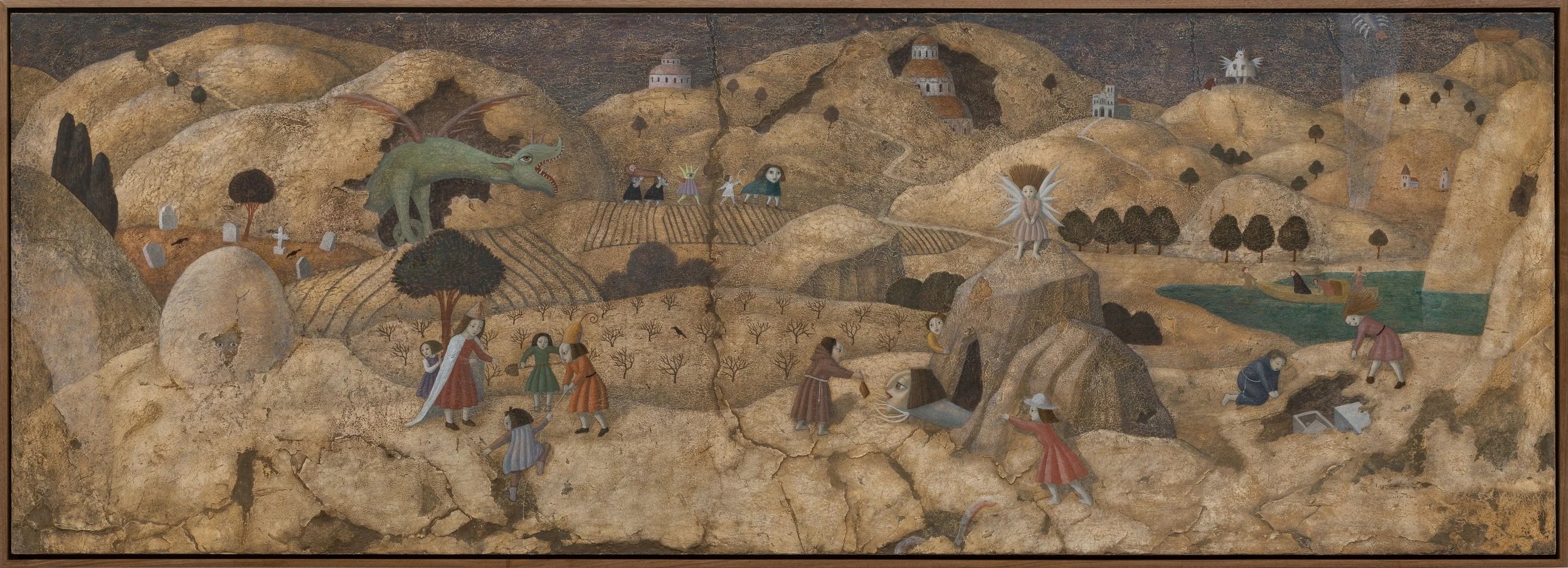

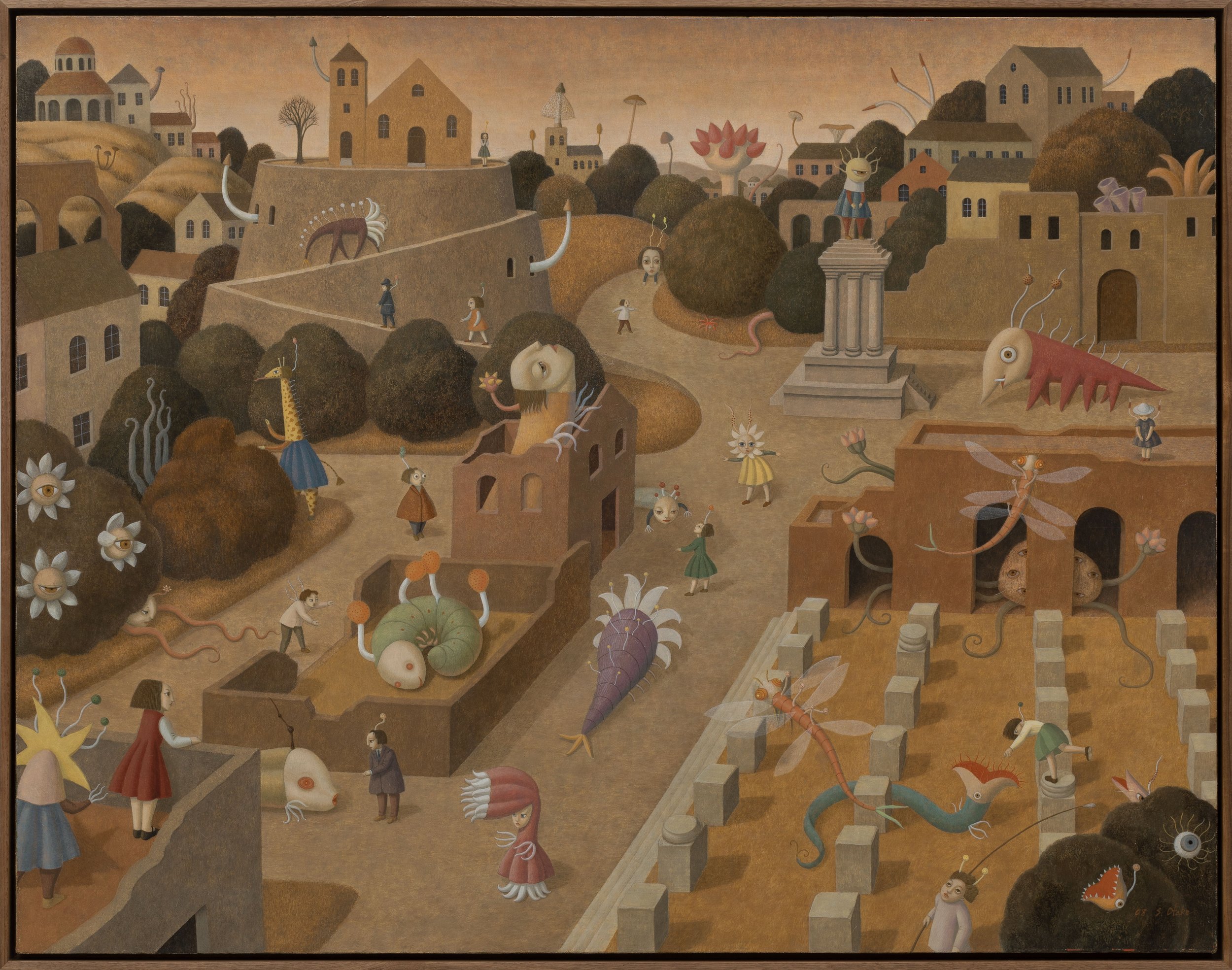

It is fitting to recognize Shigeo Otake as a cultural figure representative of his time. His creative journey, spanning over forty years in the suburbs of Kyoto, has woven together a rich visual language that touches on diverse fields such as art history, literature, religion, folklore, and astrology. In Otake’s world, which remains closely tied to the earth’s surface, his paintings depict organic forms that seem poised to engulf the planet itself. These ancient organisms, insects, amphibians, and fungi lie in wait, silent and patient. Otake peels back the layers of biological traces embedded in the Earth, revealing a vibrant tapestry of life. His work feels like that of a natural historian, using painting as a means to bring hidden spiritual entities to light.

To step into Otake’s world is to embark on an adventure that amplifies the senses. His ability to capture the intricate details of these life forms is remarkable. The textures, tendrils, and delicate structures are rendered with such precision, while the architectural elements in his works follow a carefully constructed, labyrinthine logic. His paintings teem with life, presenting an ecosystem that dissolves the boundaries between worlds. Even looking at these untouched, original creatures induces a sense of awe, as we begin to realize we might have once shared, or even continue to share, this planet with them.

The strange, ghostly figures in Otake’s work are closely tied to humanity’s early exploration of life and consciousness. The creatures in his paintings are both products of human imagination and yet possess survival traits that go beyond our understanding. Where modernism often led to fragmentation and irreversible ruptures, Otake’s path takes us elsewhere. The techniques and styles of Western painting have shaped his artistic method, evolving alongside his research into different species. Japan’s abundant natural landscape, combined with its unique “dimensional culture,” gives Otake a distinct perspective, allowing him to merge symbolic beings with the natural world in a seamless, unified vision.

Secrets of Natural History Museum, 1987. Tempera and oil on canvas, 80.3×116.7cm

II. A Confluence of Wonders

Born in Kobe, Japan, in 1955, Shigeo Otake not only witnessed Japan’s postwar economic recovery and rapid growth, but also the eventual collapse into the bubble economy. His artistic practice, set in rural areas surrounded by ancient tomb parks and shrines, took shape during the 1960s, a time when Surrealism spread across the world and mingled with Japan’s native fantasy culture. Kobe, where Otake was born and raised, was Japan’s first port city to open to the world. The rich forests of Mount Rokko and the nearby Seto Inland Sea created a layered cultural and geographical environment that reflected the creation myths from the Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters), nurturing a widespread sense of curiosity. The contradictions of Japan’s soil, much like its elusive language, absorb and transform foreign influences, turning them into new narratives. The curiosity suppressed during the war became a source of comfort for the postwar public, helping them through the chaos and anxiety of the time, while also becoming a wellspring of nostalgia for Otake and his peers.

Chashi, 2006. Tempera and oil on board. 21.2×33.4cm

Narrative continuity is a distinct feature of Otake’s work. He often develops a specific theme through a series of paintings, accompanied by short allegorical phrases or cryptic lines. Through his art, Otake creates a world that blends with everyday life while remaining hidden just beneath the surface. This duality reflects his own way of life, deeply connected to the city yet always able to retreat into the forests. Using a mix of primitive symbols and imaginative creatures, Otake expresses a truth that cannot easily be defined by conventional narratives. This brings to mind the work of the Japanese writer Shibusawa Tatsuhiko, who once wrote about Salvador Dalí, offering a way to understand the cultural fusion of that era. In his work, Shibusawa references Émile Mâle’s Religious Art in France in the Thirteenth Century, which quotes Adam of Saint Victor: “What could a walnut be, if not a symbol of Christ? The green husk and flesh represent Christ’s body, his human form. The hard shell represents the place where his body suffered, the cross. But the kernel inside, which nourishes humanity, must be his hidden divinity.” Dalí, who combined his love of gemstones with Christian symbolism, wrote something strikingly similar. Shibusawa commented that medieval and Renaissance people loved interpreting symbols, and Dalí shared this inclination, always eager to find symbolic meaning in natural objects. This view also applies to Shigeo Otake. His work, deeply rooted in medieval and Renaissance traditions, is equally rich with symbols and metaphors, making it difficult to explain in simple terms.

Otake’s art draws abstract meaning from tangible objects, creating a fantastical connection between the inner self and the material world. In humanity’s search for knowledge, these metaphors and symbols may have helped shape different civilizations. In Greek mythology, the Chimera, a fire-breathing creature with the head of a lion, the body of a goat, and the tail of a serpent, continues to puzzle those who study it. This mythological being forms the foundation for the inhabitants Otake creates for his alternate worlds. Similarly, Japan’s fascination with Godzilla during the Heisei era reflected fears about the destructive power of war. The deeper Otake explores these ambiguous realms, the more intricate and wondrous his creatures become. Cerberus, the three-headed hound of Hades, the many-headed Hydra, and the Sphinx are all part of the same mythological family as the Chimera. They trace their origins to humanity’s ancient fears of volcanic eruptions, the sea, and divine punishment.

Though Japan and Western Europe are geographically distant, they share unexpected similarities in their views of gods and spirits. Japan’s narrow land and abundant forests have fostered a complex system of deities, from Princess Kaguya in The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, to Momotaro, the Peach Boy, and other figures from local folklore. Even everyday objects, when imbued with human spirit, transform into tsukumogami, and lead the Hyakki Yako (Night Parade of One Hundred Demons). Although Japan’s mythology is deeply connected with that of its neighbor China, it follows a distinct path, diverging from China’s avoidance of supernatural themes. In Western Europe, classical stories from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, combined with the animistic beliefs of Germanic, Slavic, and Celtic cultures, influenced the fantastical creatures carved into medieval cathedrals. These figures reflected a mixture of religious law and fear of foreign invaders, just as Japan’s gods and spirits grew from daily interactions with nature. Europe’s encounters with other cultures led to more structured, text-based mythologies, while Japan’s spirit world evolved through direct experience with the natural world.

Amabie is Here,

2020.

Tempera and oil on board.

27.3×22cm

Amabie is a yōkai from late Edo-period Japan, said to possess the power to prophesy the future and ward off epidemics. As a unique figure in Japanese folk belief blending art, spirituality, and yokai culture, Amabie re-emerged as a symbol of hope and health on Japanese social media during the COVID-19 pandemic. This work was created by Shigeo Otake during the pandemic, inspired by the legend of Amabie.

III. The Italian Wave and the European Journey

In 1974, Shigeo Otake entered Kyoto City University of Arts, where the entire institution was swept up in an “Italian wave.” Many painters in the fine arts department embarked on study trips to Italy. Koji Yamazoe, a prominent figure in the Western painting department, traveled to Italy and Spain, where he enthusiastically studied classical Western painting techniques like fresco (affresco) and egg tempera. In 1976, Otake joined the oil painting and mural class, following in the footsteps of Professor Yamazoe.

At this time, Surrealism, born from the chaos of war, had evolved into a global art movement. It was accompanied by breakthroughs in psychology from Freud and Jung, literary explorations of consciousness by Joyce, Woolf, and Faulkner, and Surrealism’s influence on poetry. In 1960s Japan, intellectuals eagerly translated and introduced irrational and surreal elements from European literature, gradually realizing that the “fantasy” that had developed locally was part of a broader international system.

Since the Meiji period, Japan’s maritime civilization created a mirror image of the West, where foreign power was not seen as an invasion but rather as a catalyst for shedding old traditions and embracing distant cultures into its own system. The art academies played an active role in introducing and training artists in Western techniques such as printmaking, egg tempera, and traditional religious art. At this point, Europe was still a distant, postcard-like image for Otake. In 1977, he took a leave of absence to embark on a two-year journey through Europe, determined to see the visual systems of the other side of the ocean up close. In a photograph of the map he carried, he marked the places he visited during this trip. Given the lasting influence of this journey on his later work, here is an outline of his route:

“I set out with two classmates from the mural class at Kyoto City University of Arts, with plans to visit major museums and churches in Western Europe. We started in London, England, and then took a boat to the Netherlands, traveling south through Belgium and France. In France, we mainly visited Gothic and Romanesque churches. I parted ways with my companions in Spain and began traveling alone. After a brief stop in Morocco, I arrived in Italy, where I focused on viewing Renaissance frescoes. Initially, I had planned to stay for about three months, but as I became accustomed to traveling and learned how to economize, I ended up staying for around six months. From there, I traveled through Yugoslavia to Greece, and then visited Austria, West Germany, East Berlin, Switzerland, and finally returned home through Paris. Despite some unexpected disruptions, I was able to achieve my goal of seeing as much Western art as possible, which I believe became the foundation for my later artistic work.”

A map provided by Shigeo Otake, documenting his travels in Europe during the 1970s.

Indeed, over the course of those two years, Otake immersed himself in Europe’s rich and vibrant cultural landscape. He absorbed the grandeur of temple ruins, the sanctity of church frescoes, and the majesty of palace architecture, all of which formed a solid foundation of humanism that surrounded him. Much like the story of Saul’s transformation into the Apostle Paul, Otake’s experience of sculptures and paintings seemed to strip away the veils that obscured his vision. The vivid depictions of divine figures, brought to life through sculpture and painting, left a lasting impression. Otake understood that it was the diverse belief systems behind these works that built this cultural fortress.

In 1978, Otake returned to Japan and resumed his studies at Kyoto City University of Arts, completing both his undergraduate and graduate programs in fine arts. His deep engagement with classical techniques and his mastery of visual language set him apart from his peers. Additionally, during the 1980s, Otake traveled to China, Egypt, Israel, and Eastern European countries such as Romania, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. The influence of these journeys never left his work. Otake often revisits his notes and sketches from these travels, allowing the memories of those vibrant experiences to come alive once again.

Shigeo Otake at the Herodium archaeological site, Bethlehem, Israel, 1985.

IV. The Speculative Jungle

Exploring Shigeo Otake’s works from the 1980s through the next twenty years is like stepping into a visual jungle shaped by figures like Paolo Uccello, Giotto di Bondone, Sandro Botticelli, and Giorgio de Chirico. For Otake, the emphasis on symbolism in European medieval and early Renaissance art reflects a shared intellectual rigor: the blending of narrative, the exploration of technique, and the focus on metaphysical meaning. This seemingly rigid style, however, becomes the perfect framework for capturing the essence of Japan’s yokai (spirit) culture. From the very beginning, Otake appeared to consciously adopt the higher-level metaphors and symbolic expressions offered by Western styles as a means of building his otherworldly kingdoms. In other words, the masterpieces of Western art became the ideal habitat for the strange inhabitants of Otake’s worlds.

Untitled, 1982. Tempera and oil on canvas. 53×65.2cm

In his works, Otake often places miniature images of real-world creatures within the composition and hints at their origin in the titles, signaling that the worlds he portrays exist somewhere between reality and illusion. The early inhabitants of Otake’s work mostly come from the ocean. Creatures like sea anemones, swaying with venomous tentacles, create a striking contrast between their enchanting appearance and their deadly hunting tools. Or ammonites, long gone from the Earth along with the dinosaurs, whose shells make up their heads and bodies, with luminous, flexible soft tissue that serves both as hunting instruments and as dancers in eerie nocturnal performances. As Otake delved deeper into the natural world, insects and amphibians with extraordinary abilities began to appear in his paintings. What’s intriguing is that many of the species Otake selects reflect humanity’s ancient, primal ideas about life, death, and rebirth. The sacred scarab beetle of ancient Egypt, for instance, rolling its ball like Sisyphus, was a symbol of the sun’s daily journey in the sky, and its lifecycle, from egg to adult beetle emerging from the ball, corresponded to the twenty-eight-day lunar cycle, making it a symbol of resurrection. Before humans had access to the world of microscopic life, the transformation of creatures like butterflies or cicadas seemed nothing short of miraculous. Otake’s work is infused with this kind of contemplation.

A 1981 work by Shigeo Otake based on Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens (archival image).

Attirement of the Bride (1940), oil on canvas, 129.6 × 96.3 cm, by Max Ernst. Currently housed at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice.

In his early works, the mutated forms of his inhabitants share similarities with the works of Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst, particularly Ernst’s Attirement of the Bride, created in 1940 under Carrington’s influence. In 1981, Otake produced a large-scale work inspired by Raphael’s School of Athens, where the species moving through a hybrid architectural landscape seem to hover between Carrington’s ethereal visions and Ernst’s mysterious characters. The “inhabitants” of Otake’s painted world dwell within recognizable medieval and Renaissance settings. This particular work brings together elements like birds preaching, the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary, the Three Graces, and Hieronymus Bosch’s chaotic depictions of the human condition in The Garden of Earthly Delights. The deeper one looks into Otake’s compositions, the more they radiate an aura of mystery, as a utopian academy of philosophers is transformed into a gathering place for wizards clad in nature’s camouflage.

Otake’s 1985 painting Dancing Partner provides another example of the early threads in his work. It was inspired by Paolo Uccello’s series of paintings, created between 1467 and 1468, which depict the desecration of the Eucharist. In Uccello’s composition, narrative elements are set against a backdrop of architectural spaces and nightscapes, with six chapters framed by red columns. Uccello’s works are characterized by dreamlike figures, vibrant colors, and his groundbreaking studies of perspective, as well as his remarkable ability to craft a continuous narrative. In Otake’s homage, he strips away Uccello’s obsession with perspective but retains the basic architectural structure. The woman selling the Eucharist and the Jewish buyers are replaced by creatures resembling sea anemones and unicorns, while the scales in the original background are transformed into a frightened specimen, possibly hinting at the fate of the captured girls. In The Temptation of Homemade Sausages, also from 1985, soldiers symbolizing violence are replaced by bizarre demons, and the foreigners roasting the Eucharist over a fire are turned into witches. Otake transforms the conflict between human civilizations into a reflection of the natural world’s cycle of hunting and survival.

Dancing Partner, 1985. Shigeo Otake. Tempera and oil on board. 27.3×45.5cm

The Miracle of the Desecrated Host (detail), 1467–1468, tempera on panel, 43 × 351 cm, by Paolo Uccello. Currently housed at the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche in Urbino, Italy.

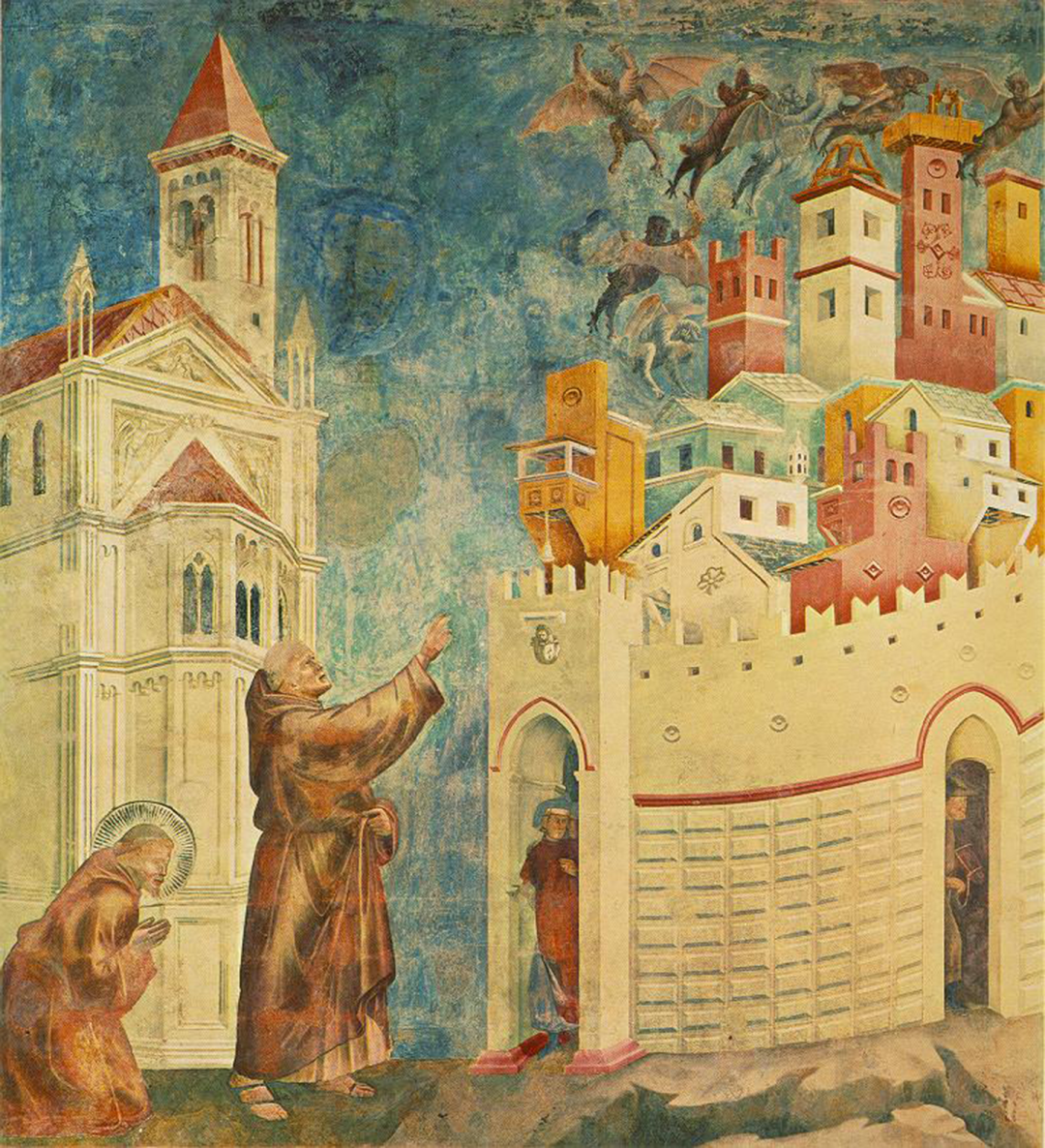

Examples of this kind abound. Otake’s 2009 work St. Francis Driving Out the Demons is a tribute to Giotto’s fresco cycle of 28 scenes in the Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi. Giotto’s acute observation of nature breathes life into the otherwise rigid medieval style. Although this scene of St. Francis shares similarities with stories from other religious traditions, such as those of the Buddha, it is Giotto’s connection to St. Francis as a contemporary that gives the work its power. In Otake’s version, the background is simplified, while the demons are vividly depicted. The birds following St. Francis symbolize his successful preaching to the animals, a theme Otake had explored in earlier works. Similarly, Otake’s Execution at the Monastery of St. Catherine, also from 2009, draws inspiration from the sacred site in the Sinai desert. Much like his St. Francis piece, Otake merges the famous icon The Ladder of Divine Ascent with the monastery’s architecture, transforming the struggle with demons into an ever-present haunting force. The original confrontation is replaced by a dreamlike sense of ascension.

St. Francis casting out demons, 2009. Shigeo Otake. Tempera and oil on board. 24.3×33.4cm

Legend of St. Francis: 10. Exorcism of the Demons at Arezzo, 1297–1299, fresco, 270 × 230 cm, by Giotto di Bondone. Currently housed in the Upper Church of the Basilica of San Francesco, Assisi, Italy.

If Otake’s smaller works serve as windows into the past, his 1996 painting On the Road to Santiago de Compostela offers a larger framework for understanding his homages. Santiago de Compostela, believed to be the resting place of St. James, became a destination for medieval pilgrims after the saint’s tomb was discovered by a monk following the Milky Way. The construction of the cathedral transformed the site into the ultimate goal for pilgrims during the Middle Ages. In Otake’s painting, he magnifies and distorts the buildings along the pilgrimage route, creating powerful visual impressions. He replaces the traditional symbol of the pilgrimage, the scallop shell, with the spiral shell of a snail. The soft-bodied creatures living within these shells have long symbolized the soul and the body, the womb and the grave. The juxtaposition of the empty shell in the foreground with the distant destination mirrors the pilgrimage itself, as travelers and strange creatures, laden with symbolism, make their way across the starry field.

Road to Santiago de Compostela, 1996. Tempera and oil on board. 130.3×193.9cm

In addition to his works inspired by religious sites, Otake subtly incorporates elements from Botticelli’s flowing lines and de Chirico’s surreal, shadowy landscapes into his fantastical world. These elements quietly shape the atmosphere within his paintings. Otake’s exploration of technique also continues. His 1996 work Heritage reflects a thoughtful meditation on Western methods and styles. What makes this piece particularly special is Otake’s use of a fresco transfer technique. Since frescoes are painted directly onto walls, moving them requires peeling the surface layer of the wall and transferring it onto a new material. Typically, an adhesive is applied to the surface, and once the fresco is removed, it is transferred to a new base, and the adhesive is then dissolved. In Heritage, Otake depicts an ancient ruin that has now become a playground for children on a treasure hunt. This structure of looking back at the past is echoed in Otake’s later works, where humanity looks at present-day ruins from a future perspective.

Heritage, 1996. Tempera and oil on board. 63×180cm

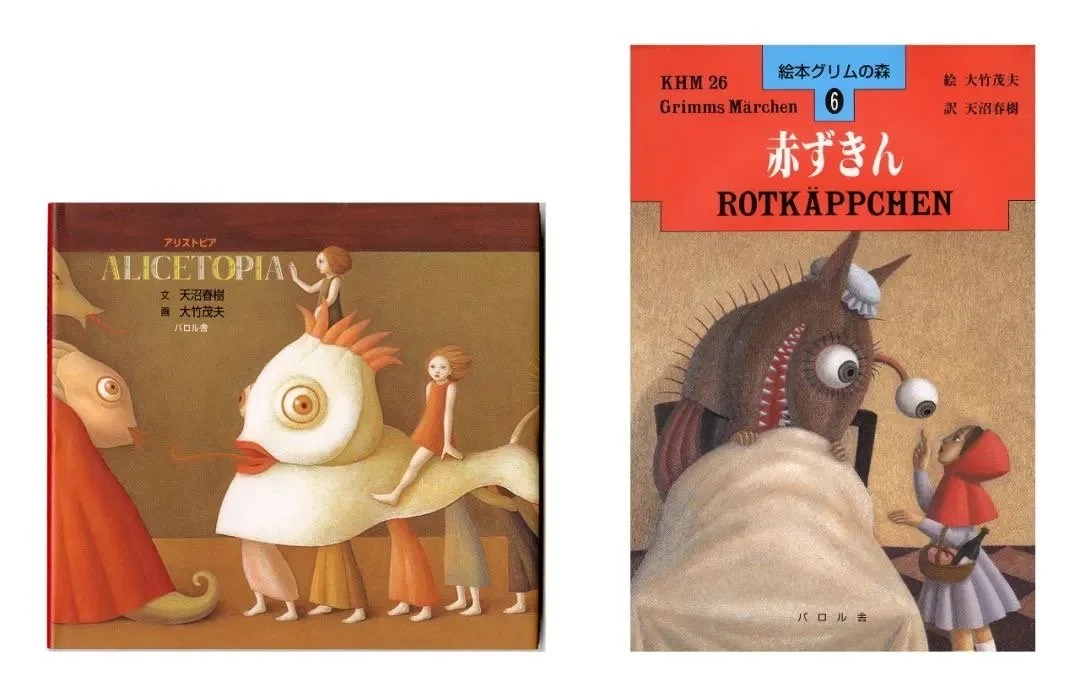

V. The Subway and Beyond

In the 1980s, Japan was regarded as the leader in Asian publishing. A significant wave of European literature flooded the Japanese market, and in 1988, Shigeo Otake collaborated with the science fiction publishing giant Hayakawa Shobo. Over the next decade, many of Otake’s paintings were featured as covers for the Japanese translations of several works by the renowned American educator Torey L. Hayden. Otake also created a series of paintings based on two classic literary themes, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Little Red Riding Hood. In 2000 and 2005, Otake collaborated with writer Haruki Amanuma to publish two picture books, Alicetopia and Rotkappchen (Little Red Riding Hood), through Parolsha Publishing. Alicetopia draws together Otake’s paintings from 1980 to 2000, with Amanuma’s cryptic text providing the perfect counterpart to Otake’s intense visual imagery. Inspired by Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures Underground, Amanuma reinterpreted Otake’s works as gateways to different exits from reality, each wrapped in complex layers of time and space. If Carroll’s story was born out of a world adjusting to the standardization of time and the need to synchronize with clocks, Alicetopia explores the unsettling new landscapes brought on by the acceleration of industrialization and the opening of underground passages in the 1860s.

Alicetopia (2000) and Rotkappchen (2005)

The book begins in a subway, where a young girl is trapped within the puzzling introduction written by Carroll. Seated on either side of her are creatures transformed into hybrids of sea anemones, poppies, and multi-eyed monsters. In Japanese culture and mythology, the pathways into other dimensions are varied and mysterious, and before the girl realizes it, she has already entered the labyrinth of the story. This girl is neither a symbol of desire like Nabokov’s Lolita nor a real-world figure like Carroll’s Alice. Instead, she more closely resembles Virgil, who guided Dante into the underworld, or the assistant in a shamanic ritual, drawing the viewer into a particular atmosphere. Otake’s 1993 work The Last Hours of the Mobile Fungal Garden becomes a labyrinthine town in this underground world, while his 1999 piece The Waterfront serves as the gateway to the fantasy town. In the scene, a young girl, dressed in a fish-shaped disguise, waits at the shore as elders and residents emerge from the water, stepping onto the stairs to greet her. The vibrant and divine world that Peter Paul Rubens painted in The Arrival of Marie de’ Medici at Marseilles is replaced by a suspenseful, restrained atmosphere in Otake’s work. The passion of Rubens is exchanged for the cold calm of Otake’s world, with each reflecting a different cultural tone. Amanuma’s narration draws attention to the reflective surface of the water, turning T.S. Eliot’s meditation on time in Four Quartets into a spatial riddle.

Passing through spaces like mushroom houses, anatomical rooms, castles, ancient battlefield ruins, and observatories, Otake’s town is inhabited by beetle officials, mushroom sages, mysterious fungi, talking flowers, bird-like creatures, species researchers, kings, and celestial beings. These figures create a world that not only mirrors Carroll’s strange realms but also reveals glimpses of Otake’s Wilder World. At the end of Alicetopia, the girl returns to the subway, lost in thought, seemingly awaiting the next labyrinth to appear. Though this seemingly dreamlike town is woven from an assortment of images, it radiates a hidden, overarching vision. In many ways, this work, rooted in literature and classic stories, tempts the artist to continue building and expanding his own world.

Waterfront, 1990. Tempera and oil on board. 45.5×53cm

VI. The Coming of the Mycocene

Japan has a long tradition of foraging for mushrooms, and it wasn’t until the Meiji period, under Western influence, that meat became a regular part of the Japanese diet. Prior to that, the staple foods of the Japanese people were wild vegetables, mushrooms, and fish from the sea. In the Manyoshu from the Nara period, there is a line that reads, “Mushroom umbrellas rise at the foot of Mount Takamatsu, filling the forest with the scent of autumn.” During the Edo period, farmers would even pre-place matsutake mushrooms for the wealthy to collect as part of a leisurely activity. The fragrance of mushrooms has long been an autumnal symbol in Japanese literature. After graduating from Kyoto City University of Arts in 1981, Shigeo Otake moved to the western suburbs of Kyoto, where he rented a house and studio with friends. Every autumn, Otake would go out to forage for mushrooms, relying on an edible mushroom guidebook, and the bounty he collected enriched his daily meals.

Macrolepiota procera, Kyoto, 1985

This photograph captures a specimen of Macrolepiota procera (Parasol Mushroom), which Shigeo Otake first encountered near his studio in Kyoto in 1985. The mushroom, reaching a height of nearly 40 cm, prompted Otake to consult a field guide at the local library, where he identified it as an edible species. This chance discovery not only sparked a lifelong devotion to mycology but also seeded in his mind a haunting vision of a world transformed by fungal life.

For the first few years of foraging, Otake did not incorporate these “kawaii” mushrooms into the world of his painted inhabitants. That changed in 1985, when Otake stumbled upon a cicada parasitized by Cordyceps at a local shrine. Watching the fungus slowly invade the cicada nymph’s body, draining its energy and turning it into a puppet and an empty shell, Otake witnessed the spores sprouting from the soil with the coming of spring, carried away by wind and rain. This opened Otake’s eyes to the vast and ever-expanding world of underground fungi. The endless variety of fungi and their hosts, with shapes both eerie and boundless, surpassed even the chimera-like creatures of human fantasy in their strange allure. The complex symbiotic and evolutionary systems that fungi created sparked Otake’s interest in merging with this hidden kingdom.

A Miscalculation by Mycologist H.A, 1988. Tempera and oil on board. 112×162cm

From The Mobile Fungal Garden (1988-1993) and Fungal Tarot (1995–) to The Mycocene (2004-2005), Otake wove together a complete narrative about the world of fungi. A mobile fungal garden makes an unexpected visit to a human town, and after being infected by the spores, the townspeople begin to grow fungi themselves. Despite their efforts, humanity is unable to stop the endlessly spreading infection. In the end, humans choose to gather the remnants of their consciousness and, after several failed attempts, merge with the fungi, creating a new species called the “Fungal-People.” The depth of The Mycocene lies in Otake’s use of Dante’s Inferno as a narrative model, embedding post-human metaphors within the life cycle and reproductive strategies of fungi. If Dante’s vision of hell filled in the gaps in the Bible’s description of the underworld, Otake’s dense and expansive visual world creates a similar sense of religious tension, evoking a spiritual struggle through the complex and continuous cycles of fungal growth.

The Last Days of the Mobile Fungi Garden, 1993. Tempera and oil on board. 53×72.7cm

Otake’s still-evolving Fungal Tarot series was originally inspired by John Dickson Carr’s mystery novel The Eight of Swords, in which tarot cards play a key role in the unfolding story. Otake, however, was less interested in divination than in drawing parallels between the bizarre and ever-changing forms of fungi and the symbolism of the tarot cards themselves. If icons depict the relationship between humans and the divine, tarot cards, based on allegory and symbolism, reflect humanity’s interaction with the material world. For Otake, tarot cards serve as a bridge between the fungal kingdom and the human mind, offering a portal through which viewers can enter the strange and fascinating world of fungi.

Two of Wands, 2010. Tempera and oil on board. 22.7×15.8cm

King of Cups, 2014. Tempera and oil on board. 22.7×15.8cm

VII. Epilogue

In the final chapter of The Mycocene, the "Fungal-People" develop a technique that uses fungi as a medium to merge multiple life forms. With this technology, they can easily travel through the sky, dive into the seas, and even explore outer space. On sunny holiday afternoons, the "Fungal-People" visit the Human Memorial Park, where they reflect on the remnants of the long-extinct “Old Humans.” Much like Urashima Taro returning from the Dragon Palace, the narrative ends with a feeling of emptiness, hinting at something yet to emerge. We find ourselves in the midst of the Anthropocene, seemingly open but, in reality, trapped within a systematic network built on logic and mathematics, leading humanity toward irreversible closure and accelerated collapse. Since the start of the millennium, the term “Anthropocene” has frequently been invoked—what appears to be a scene of victory may, in fact, be a signal of impending disaster.

In 2009, Shigeo Otake appeared on NHK's documentary series Passionate Moments: Hobbies Amidst a Busy Life – The Cordyceps Episode, where he left a lasting impression on the audience as a painter passionately devoted to Cordyceps. As a member of the Japan Cordyceps Enthusiasts Society, Otake contributed to The Cultural History of Cordyceps, published in 2012 by Ishida Taiseisha. The story of fungi continues to evolve, and Otake’s intricately imaginative fungal world not only connects his local practice with humanity’s endless search for understanding but also embeds the symbols and allegories hidden within the world of Cordyceps. The future that Otake portrays in his paintings prompts reflection—it suggests that the answers to humanity’s crises may have already been written long before the problems appeared. For Otake, he is simply unveiling a hidden world that has always been present.

Human Memorial Park, 2008. Tempera and oil on board. 90.9×116.7cm