Cordyceps Notebook

Shigeo Otake

2006 − 2008

Ophiocordyceps sobolifera - March 2006

Lately, I haven’t seen Ophiocordyceps sobolifera around at all. Last year, not a single one. In Japan, this species is often treated as the face of Cordyceps fungi.

Strictly speaking, “Cordyceps” refers to Ophiocordyceps sinensis, a parasitic fungus that grows on ghost moth larvae in the high mountains of China. But in Japan, the word has come to refer more broadly to any fungus that grows out of insects.

I started hunting these fungi, or mushikusa as I prefer to call them to keep things simple, about seventeen or eighteen years ago. Back then, you could find O. sobolifera fairly easily around the local temples and shrines near my studio, especially during the rainy season. Sometimes ten or even twenty would appear at once. I used to dig them up and soak them in liquor to make cicada fungus sake, or harden them in varnish to use as materials in my work. It felt like a perfectly ordinary species. But about ten years ago, their numbers began to decline. Now, it has become rare to find even one.

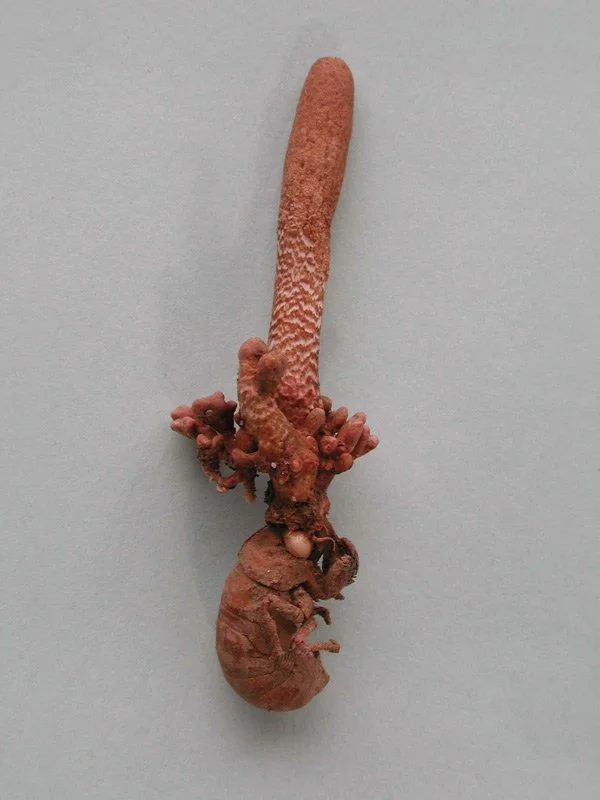

Ophiocordyceps sobolifera (mature form)

Ophiocordyceps sobolifera grows on the nymphs of the cicada Platypleura kaempferi. It produces a fruiting body 2 to 8 cm tall, with a slightly swollen, cylindrical tip measuring 6 to 28 mm long and 4 to 6 mm wide, pale brown to orange-brown in color. The stipe is cylindrical and slightly paler, about 3.5 to 4.5 mm thick.

Was it because I overharvested them? I doubt it. I only collected seriously during the first two or three years, and even then I barely touched the population. And even after I stopped collecting, they kept showing up every year.

So what happened? The cause is pretty clear. The host species, Platypleura kaempferi, the small cicada known as the Niinii-zemi, has disappeared from the area.

Cordyceps fungi are said to be host-specific. One species of fungus grows on one species of insect. That is the general idea. But in reality, some Cordyceps can infect a range of insect hosts. Even among cicada fungi, species like Ophiocordyceps japonensis or Ophiocordyceps heteropoda can parasitize multiple types of cicadas. But O. sobolifera only grows on the Niinii-zemi. When the host disappears, the fungus has no choice but to vanish with it.

Ophiocordyceps sobolifera

Ophiocordyceps sobolifera is typically found on the ground in gardens, temple grounds, and low mountain forests, appearing from May to August. Its distribution includes Japan, China, the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand.

The Niinii-zemi is a semi-urban species. It thrives in environments like old Japanese neighborhoods, where cars are few and patches of bare earth still exist. Unlike forest-loving species like Tanna japonensis or city-adapted ones like Graptopsaltria nigrofuscata and Cryptotympana facialis, the Niinii-zemi needs that in-between kind of place. But as development expanded and traffic increased, it was pushed out of the cities and into the hills. And the fungus, it seems, could not follow. There is probably a metaphor in that somewhere, but nothing comes to mind at the moment.

Maybe when something does, I will make a painting about it.

The painting shown here is not directly related to this story. It was made back when O. sobolifera still appeared regularly. I remember digging carefully, wondering how deep I would have to go before uncovering a cicada, heart racing the whole time.

The Man of Ophiocordyceps sobolifera, 1999. Tempera and oil on board. 17.9×13.9cm

Tilachlidiopsis nigra - May 2006

People tend to think of Cordyceps as something extremely rare, but not all of them are. There are plenty of common species too, like Ophiocordyceps nutans, which grows on ants, and Purpureocillium atypicola, which grows on spiders. Even Ophiocordyceps sobolifera, the cicada fungus, used to be considered common not long ago.

One species, Tilachlidiopsis nigra, parasitizes ground beetles of the genus Carabus. Although it is officially listed as a common species, I spent over ten years searching for it without ever encountering one. There are many Cordyceps fungi that grow on beetles, but most of them emerge from larvae. Very few infect adult insects. This fungus is one of those rare exceptions. It can also grow from larvae or pupae, but the most striking specimens come from adult beetles. When it emerges from the glossy blue-green body of Carabus insulicola, the result is so beautiful I could frame it. The fungus itself is wiry and black, tough enough to hold its shape even after drying.

Tilachlidiopsis nigra

Tilachlidiopsis nigra produces fruiting bodies from various parts of the ground beetle’s body, including the larva, pupa, and adult stages. This is an anamorphic form, generating asexual conidia. The stipe is black, wiry, and slightly glossy, typically reaching 1.5 to 5 cm in height above ground. The tip appears as a white sphere or cotton swab-like structure. It is commonly found from June to October in shrine grounds, temple steps, stone walls, and deciduous forests.

And yet, after all those years of searching, where did I finally find my first Tilachlidiopsis nigra? Right in the heart of Tokyo. Every summer, I used to take part in a group show in Tokyo. I usually show up for the opening party on the first evening, but since people don’t really gather until later in the day, I often drop off my things at the gallery and wander around the city for a bit. About six years ago, I had read somewhere that ground beetle fungi had been spotted in Tokyo. So I decided to check out various parks and shrine grounds across the city. Sure enough, even in places like Ueno Park, I found plenty of spider fungi. That year I didn’t manage to find T. nigra, but it felt promising.

The following summer, I finally found it. In a shrine in the middle of the city, on a patch of exposed dark soil along a slope, I spotted several tiny white pins sticking up in a row. I held back my excitement and took a few photos, then started digging carefully with the small screwdriver I had brought. The soil was surprisingly soft, and out came a lump of black dirt. For a second, I thought I had accidentally broken it. But as I brushed the dirt away with my fingers, something shiny and green-blue caught the light.

Tilachlidiopsis nigra

Tilachlidiopsis nigra is commonly found from June to October in shrine grounds, temple steps, stone walls, and deciduous forests.

Since then, I’ve started finding them all over the city, year after year. Now I can believe why it’s called a common species. But it’s also true that I’ve never once found it in the western hills of Kyoto, where I live. Most field guides are written based on eastern Japan, which might explain the gap. Another species that’s supposed to be common, Ophiocordyceps tsukutsukuboshi, is also almost never seen in my area. On the other hand, Ophiocordyceps annulata, which is quite common around here, is described as rare in some field guides.

The painting shown here was made to commemorate my first encounter with Tilachlidiopsis nigra. I also included Purpureocillium atypicola, the spider fungus, because it really was growing nearby. The beetle depicted is Carabus insulicola, a species found in eastern Japan. In western Japan, T. nigra grows on a different species of ground beetle.

People of Tilachlidiopsis nigra, 2001. Tempera and oil on board. 22.7×15.8cm

Cordyceps kusanagiensis - July 2006

Let me introduce a rare Cordyceps species. It’s called Cordyceps kusanagiensis. Chances are most people have never seen it, or even heard of it. According to one Cordyceps field guide, it has only been found at Kusanagi Onsen in Yamagata Prefecture and is considered extremely rare. So imagine my surprise when, in May of 1999, I found this elusive fungus in the satoyama woods of Nagaokakyo City, just outside the urban area.

Cordyceps kusanagiensis

This extremely rare ground-dwelling species parasitizes moth pupae. The fruiting body is loosely tamp-like in shape. The stipe is cylindrical, 1 to 3 mm in diameter, and may occasionally bear fine hairs. The tip is obovoid, measuring 3 to 4 mm in height. The perithecia are initially covered in a white coating, which later disappears to reveal exposed orange-yellow ostioles.

In Japan, there are about twenty places known as A-grade Cordyceps sites. These are locations where multiple species are reliably found year after year and sometimes even lend their names to the fungi discovered there. Kusanagi Onsen is probably one of them. The further down the scale you go, from B to C to D, the lower the variety and reliability. A D-grade site is where you’re lucky to find even one specimen. The area I often explore, the satoyama region along the K River in Nagaokakyo, was at the time the kind of place where you might occasionally find a common species or two. In my estimation, it was C-grade at best, maybe even D.

That March, I happened to find a species of Cordyceps parasitizing gall midges. Encouraged, I searched more carefully and managed to find Ophiocordyceps ryogamimontana, a dragonfly fungus. I began to think maybe this field wasn’t so hopeless after all, and I started going out earlier than usual that spring. Around mid-May, while exploring a ravine in search of dragonfly fungi, I came across a spot where the water was too deep to cross. I climbed up the bank to go around, and as I reached for a tree root for support, I noticed a pale club-shaped object about a centimeter long near the base of the root. When I looked closer, I saw a textured surface, tiny bumps. It hit me instantly. Cordyceps. I held on to the root with one hand and carefully dug it out with the other. It was emerging from a dark cocoon, likely belonging to a moth. I found several more and brought them home. When I sent the specimens to a specialist for identification, the response came back quickly and with great surprise. It was Cordyceps kusanagiensis.

Maybe my field wasn’t C or D-grade after all. Maybe the problem was me. Based on what I know now, I would rate it a B-grade. That same year, I also discovered Ophiocordyceps hayakawaensis and Ophiocordyceps clavulata, two species I had never seen before. I guess I had leveled up as a Cordyceps hunter.

Sadly, the place where I first found C. kusanagiensis stopped producing it just two years later. I might have overharvested it that first year, but more than likely, it was the instability of the terrain. A landslide had altered the landscape.

Cordyceps kusanagiensis

Cordyceps kusanagiensis typically appears between July and August in forested areas among shrubs such as Weigela hortensis and Euonymus alatus.

The next time I encountered the fungus was in April 2004. While walking along a hiking trail, I spotted a stark white, club-like structure growing on a slope. I dug it out and sure enough, I found that familiar cocoon. It wasn’t mature yet, and the surface hadn’t formed the tiny nodules, but there was no doubt. It was Kusanagi. I quickly reburied it, hoping to return when it was fully developed. But when I came back a week later during the Golden Week holidays, it was gone. Only a stem remained. Judging by the break, someone had snapped it off. The trail was popular so maybe a passing hiker had broken it without realizing what it was. Disheartened, I searched the area again. Luckily, I found several others. The following year, nearly ten emerged from that same slope. It looked like the area might become one of the few stable habitats of this rare fungus.

Just when things seemed hopeful, disaster struck. In February of this year, I returned as usual to check the site, and I couldn’t believe what I saw. A fifty-meter stretch of the slope, including the exact spot where the fungus had grown, had been completely stripped away. It was roadwork. They were expanding the forest path. And just like that, this rare fungus, the kind you might expect to see listed in the Red Data Book, became a phantom once again.

This May, I revisited the area and found a single specimen. It was growing just a little beyond the part that had been cut away. Because it was in a highly visible spot, I gently covered it with a fallen leaf.

The painting here was made to commemorate that initial discovery. I had the impression of the fungus rising from cocoons buried together in a landslide.

People of Cordyceps kusanagiensis, 1999. Tempera and oil on board. 22.7×15.8cm

Ophiocordyceps jinggangshanensis - September 2006

With enough years of observing nature, you start to develop a kind of calendar in your mind. It’s not just for mushrooms or insects. For example, when I hear the cherry blossoms have reached Shikoku, I know it’s time to start looking for Morchella angusticeps. When Golden Week ends, I plan a visit to that shrine because Phallus indusiatus might be emerging. Each season brings familiar faces, and I find myself quietly looking forward to seeing them again.

For Cordyceps, in my usual field, the spring season begins with Isaria and other fungi-based species that emerge alongside the cherry blossoms. Around Golden Week, Cordyceps kusanagiensis and Cordyceps militaris begin to appear. Then come Ophiocordyceps nutans and Ophiocordyceps japonensis, followed by Ophiocordyceps annulata in June. In Tokyo, Tilachlidiopsis nigra probably starts showing up around that time. When the rainy season arrives, Purpureocillium atypicola enjoys its brief reign. As the rains end, Ophiocordyceps sobolifera and many others start appearing all at once. In dry August, it’s time for the aerial spider-infecting fungi that cling to the undersides of riverbank leaves. September rains bring another brief flourish, and in deep autumn, species like Cordyceps dipterigena and Ophiocordyceps stylophora begin to send out immature spikes for overwintering. In winter, the fields go quiet, ruled only by the threadlike Ophiocordyceps on tiny ants.

In short, I usually have a pretty good sense of what species will appear where and when. But some fungi never seem to care about the calendar.

Ophiocordyceps jinggangshanensis, for example, is considered rare nationwide. But in my local K River field, I find three or four every year. With dozens of thin stromata sprouting from the body of a geometrid caterpillar, it looks like some creature from outer space. It’s one of my favorite Cordyceps.

Ophiocordyceps jinggangshanensis

Ophiocordyceps jinggangshanensis is an aerial species that grows in large numbers on the body segments of geometrid moth larvae. The fruiting bodies are needle-like, measuring 5 to 7 mm in length and 0.5 to 0.7 mm in diameter. They are dull-pointed, with a pale yellowish-gray stipe and a light brown fertile area near the middle. It appears from July to August on tree branches in deciduous forests and is considered rare.

The strange thing is, you can’t find it by looking. It just shows up when it wants to. The usual Cordyceps rule is, once you find one, you should search the area thoroughly. But that doesn’t work with this one. It always appears alone. Another common rule is to revisit places where you’ve found a species before. Again, not with this one. I’ve never found it in the same place twice.

It does have a season. Around May, it starts producing thin white immature stromata, and it reaches maturity in July or August. But the fruiting bodies last quite a while, often staying attached to branches long after they’ve released their spores. That means you might even find them in winter, dry and brittle. It’s the kind of fungus that truly fits the phrase, now you see it, now you don’t.

Ophiocordyceps jinggangshanensis

One reason may be its camouflage. The host caterpillar clings to branches like a twig, and the fungus itself looks like a dried flower stalk or aerial root. Anyone unfamiliar would probably walk right past it without even noticing.

You also have to consider how mobile the host is. These caterpillars move more than you’d think. There’s probably a decent amount of time between infection and the fungus starting to grow, during which the caterpillar can crawl far from where it first picked up the spores.

The painting shown here captures the feeling of how this Cordyceps always appears at the most unexpected moments.

The Man of Ophiocordyceps jinggangshanensis, 1999. Tempera and oil on board. 15.8×22.7cm

Cordyceps prolifica - November 2006

People sometimes ask me, “What’s the largest Cordyceps you’ve ever collected?”

If we’re talking about host size, then Cordyceps ishikarianus, which grows on carpenter moth larvae, can reach seven or eight centimeters. Add the fruiting body, and the total length goes beyond fifteen centimeters. In terms of volume, Ophiocordyceps japonensis might win. Ophiocordyceps brunneipunctata is also a heavyweight, both in host and fungus.

But if you go by length alone, there’s one species that outdoes them all: Cordyceps prolifica. Usually, it’s around ten centimeters long, but occasionally it produces giants over thirty centimeters. Only the tip, about two centimeters, breaks through the surface. The visible part is a blunt-tipped spike covered in yellowish-brown perithecia. Despite being a fairly common species, its dull coloration makes it hard to spot.

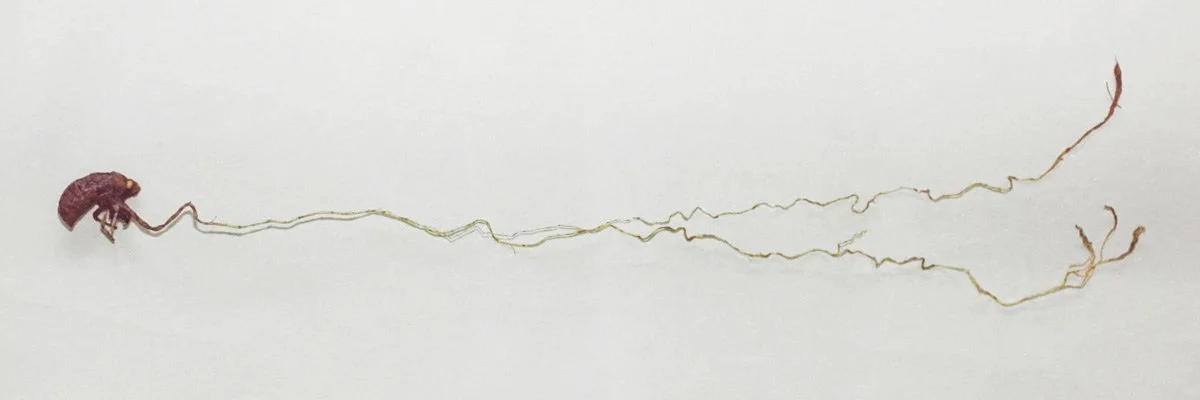

Cordyceps prolifica

Cordyceps prolifica parasitizes the nymphs of cicadas such as Higurashi (Tanna japonensis), Aburazemi (Graptopsaltria nigrofuscata), and Platypleura kaempferi. The fruiting body is usually solitary, but may occasionally branch into two to four stalks. The fertile part appears at the tip of the new growth, starting pale pink and later turning light brown. It emerges on the forest floor of mixed deciduous and coniferous woods and is perennial, sometimes appearing throughout the year. Occasional population surges have been observed.

Underground, the stipe is a thin yellow-brown cord, just one to two millimeters in diameter, leading down to the head of a cicada nymph. Digging it out without snapping the stipe is extremely difficult. People say that anyone who can extract it cleanly is a first-class digger. You never know how long it is until you try, and if thirty minutes pass without finding the host, you start to regret having tried at all.

The longest one I ever collected was fifty centimeters from tip to tail. Even as a dried specimen, it still measures over forty centimeters.

The time I dug that one up was what you might call a moment of weakness. I had found a cluster of C. prolifica growing on a slope, and I told myself I’d just dig up one. There were several in a tight group, and one a little off to the side. I started with the lone one, but the host never appeared. So I switched to the cluster. At first, it looked like multiple fungi, but a few minutes in, the stipes joined underground into a single line that kept going deeper and deeper.

I had only a flathead screwdriver and a pair of nippers for cutting roots. I hadn’t brought a shovel or trowel because they’re too bulky. So I loosened the soil with the screwdriver and cleared it away with my hands. After an hour, the two stipes began to converge, and I got the feeling they were connected far below. Another hour went by, pulling out stones, clipping away roots, and finally, there it was, the cicada nymph.

Excavated specimen of Cordyceps prolifica, approx. 50 cm long.

This particular field produces some very impressive specimens of C. prolifica, but strangely enough, only the long ones grow there. I still see them often, but I’ve never again felt the urge to dig one up.

C. prolifica is a perennial species. Even after releasing its spores, the fungus remains in place, and new growths often sprout from the same body the following year. I’ve been watching one specimen for four years now, and it keeps sending up new spikes. When left undisturbed, they form quite a magnificent stand. If you don’t dig them up, you can witness this slow transformation for yourself.

The painting shown here was inspired by that exact moment of uncovering the fifty-centimeter giant.

The Man of Cordyceps prolifica, 1999. Tempera and oil on board. 16×27.3cm

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis - March 2007

Cordyceps fungi are often seen as rare and mysterious, but every so often they appear in overwhelming numbers. When unusual weather or environmental disruption causes an insect population to explode, the Cordyceps that parasitize them can also erupt in kind.

In the summer of 2006, I witnessed one such outbreak not far from my studio, in the grounds of K Temple. Hundreds of Ophiocordyceps annulata were sprouting everywhere. This species normally grows from beetle larvae inside rotting wood, yet here it was shooting up not only from logs but even directly from the soil, crowding the forest floor so densely that it was hard to find a place to step. The host beetle, Hexarthrius parryi, was crawling all over the place.

These kinds of outbreaks usually fade after two or three years, probably because the host insects themselves crash. Afterward, the fungi vanish from the site for many years.

The most dramatic outbreak I ever witnessed was that of Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, the so-called zombie-ant fungus. This species grows from the body of a tiny ant that has died clinging to the base of a tree. A slender black stalk 1 to 2 centimeters long emerges from the ant’s neck, and midway along the stalk appears a tiny black disc, the fungus’s fruiting body, only 1 to 2 millimeters across. Although it can be found throughout the year, it is easiest to spot in winter when the undergrowth has withered and ants are scarce.

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis parasitizes the necks of ants and is an aerial species that grows in oxygen-rich environments such as tree trunks or undersides of branches rather than soil or wood. The stipe is wire-like and cylindrical, ranging from 1.5 to 4 cm in height. Flattened disc-shaped fruiting bodies, 0.7 mm thick and 1 to 2.8 mm in diameter, appear irregularly along the stalk, in shades of gray or pale brown.

Starting in the late fall of 2000 and continuing into the next year, I found O. unilateralis erupting throughout the wooded hills behind K Temple. Almost every tree root in the area had several ant corpses attached, each sprouting a thread-like black fungus. Some trees had a dozen or more. In every ten-meter square patch I counted, the density was the same, hundreds of specimens. Similar outbreaks were happening across the hills along the K River, several kilometers away.

If I applied this density across the whole field I observe, we would be talking not thousands, but tens of thousands of individuals. If the same thing happened across the broader Kyoto area, the number might have reached into the millions. And yet it made no headlines. After all, a one-centimeter black fungus growing out of an ant under a tree is unlikely to catch anyone’s attention, even by the million.

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis

Ophiocordyceps unilateralis occurs from April to September on standing trees in deciduous or evergreen forests, mossy surfaces, and occasionally on rocks. Due to its hard texture and perennial nature, it can often be observed throughout the year.

Perhaps because the outbreak was so massive, it continued for another two years, albeit with somewhat reduced numbers. I began to think of O. unilateralis as something I could find any time just by glancing at the base of a tree. Eventually, I stopped paying attention altogether.

Then one day I realized that all the ants I was seeing were just dried remains from the previous years. The outbreak, once so overwhelming, had ended quietly. These days I struggle to find even ten in a season.

The painting shown here was made during the peak of that outbreak. Like in the image, O. unilateralis often appears on the underside of tree bases, in spots protected from rain and snow.

People of Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, 2001. Tempera and oil on board. 22.7×15.8cm

Cordyceps militaris - May 2007

These days, the term Cordyceps has become fairly well known in Japan. At my exhibitions, someone often sees a painting of a person with a bright stroma growing from their head and asks, “What is that?” When I answer, “It’s a fungus,” many people, even those who aren’t into mushrooms, reply, “Ah, Cordyceps.”

In the West, however, it still seems relatively unknown. Technically, there are English names like “plant worm” or “vegetable wasp,” but they aren’t widely recognized. I once tried to explain Cordyceps to an American tourist at one of my shows using those terms, and it completely failed to get through.

In Japanese mushroom field guides, there are often multiple Cordyceps species listed. Some include a dozen or more. But in Western books, you’re lucky to find two or three, and many don’t mention them at all. One of the few species that does make it into those guides is Cordyceps militaris. Among Cordyceps, which are typically regional and specific to particular hosts, this one has a global range. Aside from Cordyceps sinensis, the original Cordyceps, it’s probably the most widely known species in the world.

Cordyceps militaris

Cordyceps militaris is a globally distributed species that parasitizes the pupae of various moths underground. Its bright orange to yellowish club-shaped fruiting body, 1 to 7 cm in length and covered with wart-like structures, makes it relatively easy to spot.

Around Kyoto, you can see its bright orange fruiting bodies from around May, often growing along the slopes beside mountain trails. Despite being so common, my first encounter with C. militaris happened surprisingly late. When I first began hunting for Cordyceps, I had this idea that mushrooms only grew in summer or fall. I never thought to search in May. I found smaller, darker relatives like Cordyceps takaomontana, or lemon-yellow species like Cordyceps pruinosa, but I couldn’t find the typical C. militaris.

Then one autumn, while hiking deep in the woods, I spotted a red club-shaped fungus from quite a distance. When I dug it up, I was expecting to find a pupa underneath, but instead, it was a large moth larva. I had found it at last, or so I thought. Delighted, I brought it home and made a dried specimen. I found several more of what I believed were C. militaris growing from caterpillars and even featured them in several paintings.

Cordyceps militaris

Cordyceps militaris typically appears from summer to early autumn on the forest floor of mixed deciduous and coniferous woods.

It wasn’t until years later, when I finally started searching in spring, that I found C. militaris growing from a proper pupa, just like the ones shown in the field guides. And then, just this year, I decided to rehydrate one of my old dried specimens and examine it under a microscope. To my surprise, it wasn’t C. militaris at all. The secondary spores were too long, and the asci were short and wide. It turned out to be a completely different species, probably Cordyceps ootakensis, which is actually considered quite rare.

So it turns out that for over ten years, I had been mistaking a rare species for a common one. Despite having searched for Cordyceps for over fifteen years, I had only recently encountered a true C. militaris.

The painting shown here is from my “Mushroom Tarot” series. It represents the Chariot card. Each of the twenty-two Major Arcana cards features a different fungus, and I chose C. militaris for the Chariot because its Latin name “militaris” suggests the military, and its English name, “Scarlet Caterpillar Fungus,” reminded me of tank treads. Ironically, I painted it before I had ever seen the real C. militaris. So the fungus in this painting is actually Cordyceps ootakensis.

The Chariot, 1995. Tempera and oil on board. 22.7×15.8cm

Torrubiella. sp - July 2027

I’ve often said that there’s no real off-season for Cordyceps hunting. Still, there is one time of year when activity peaks. A few weeks before and after the end of the rainy season, large species like Ophiocordyceps sobolifera and Purpureocillium atypicola all begin to appear at once. Around that time, I start getting restless and find myself heading out to the mountains two or three times a week. The sites I visit are only a fifteen-minute bike ride away, so each trip usually lasts just a couple of hours.

By August, the forest floor has dried under the harsh summer sun, and both mushrooms and Cordyceps vanish. That’s when the hunt moves from the mountains to the rivers. I wade into the stream and carefully flip over each leaf and blade of grass along the banks, checking for anything clinging to the undersides. My main targets are spider-parasitizing fungi.

The best-known group of Cordyceps fungi is the genus Cordyceps itself. These fungi produce elongated fruiting bodies from insect hosts and form perithecia at the tips. Famous species like Ophiocordyceps sobolifera and Cordyceps militaris belong to this group. In contrast, the genus Torrubiella forms its fruiting structures directly on the surface of the host without a distinct stalk. Many species in this genus parasitize spiders, ants, or planthoppers, and most are aerial species that attach to leaf undersides or branch surfaces. Since their hosts are not buried underground, they have no need to develop long fruiting stalks. Though they lack prominent fruiting bodies, the neat arrangement of their perithecia can resemble tiny flowers, and their colors vary beautifully from species to species.

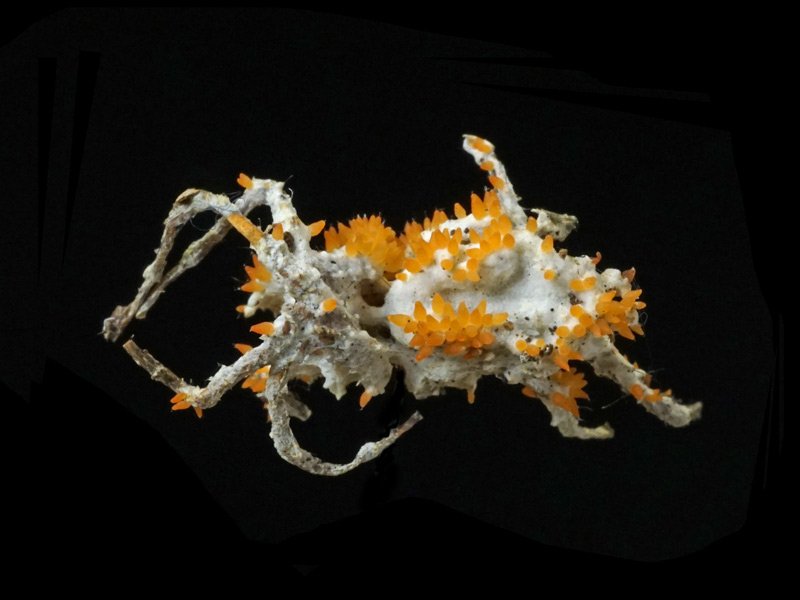

Unknown Torrubiella sp.

Fungi that parasitize spiders were once considered globally rare. However, with the clarification of the domestic distribution of the genus Torrubiella and the development of collection methods, Japan has become one of the world’s leading regions for spider-associated Cordyceps. Both Gibellula and Torrubiella complete their life cycles on the undersides of leaves in humid streamside environments. They are difficult to find without deliberate effort, but their tiny, highly varied forms and the thrill of discovery have drawn many newcomers into the world of Cordyceps.

There is also the genus Gibellula, an anamorphic group of spider-parasitizing fungi considered the asexual stage of Torrubiella. Their slender club-shaped or whip-like stalks are often covered with pale violet or white powdery conidia, giving them a striking appearance.

The K River area I often visit is a treasure trove for Torrubiella and Gibellula species. The valley splits into several narrow ravines, and each one seems to yield different species. The first to appear is usually Torrubiella leiopus, showing up around the start of the rainy season. This is followed by unidentified Torrubiella species, Torrubiella minutissima, pale yellow unknown varieties, and more, all crowding the undersides of leaves. By late autumn, most disappear, though some like Torrubiella superficialis and Cordyceps pseudonelumboides can sometimes still be found even in winter.

Torrubiella rosea

At first, I would step carefully across river stones to avoid soaking my shoes. But one day, after slipping and getting my shoes wet, I gave up and simply stepped into the stream. From that moment on, it felt like my eyes had opened. I began spotting spider Cordyceps one after another. Now I never go without rubber boots.

The painting shown here was made shortly after I began this method of searching. It shows the act of walking along the stream, looking beneath leaves for hidden spider fungi. The clustered dots represent Torrubiella, while the longer club- or whip-shaped structures are Gibellula.

Gibellula and Torrubiella, 2001. Tempera and oil on board. 27.3×45.5cm

Ophiocordyceps macroacicularis - September 2007

There is a saying that a change in place brings a change in things, and that certainly applies to Cordyceps habitats and how one searches for them. When I imagine an ideal Cordyceps spot, it’s a gentle forested slope by a stream, dotted with mossy logs and scattered ferns. I assumed that this kind of setting would be the same no matter where I went in Japan.

One year, I joined a research retreat focused on Cordyceps. I usually search alone and rarely attend group forays, but this one was held on the Tango Peninsula, a nationally renowned hotspot for Cordyceps. I decided to give it a try.

Even in outstanding sites, you cannot just show up and expect to find something. These retreats are well prepared. Local experts scout the sites in advance and lead participants toward specific targets. For this trip, the targets were species found in cedar plantations that parasitize cicadas, and a large fungus that emerges from carpenter moth larvae living at the base of Japanese knotweed.

The first site we visited was a cedar forest near the sea. The flat ground looked almost terraced, like a man-made landscape. It was hard to believe Cordyceps would grow in such a place, but sure enough, we found several Cordyceps pleuricapitata sprouting from the tidy forest floor. Next, we went to a densely overgrown field, where tall stands of Japanese knotweed rose above shoulder height. Our guide pushed through the grass toward the knotweed, and I followed without knowing what to expect. At the base of the plants, massive fruiting bodies of Ophiocordyceps macroacicularis were emerging from the ground.

Ophiocordyceps macroacicularis

Ophiocordyceps macroacicularis grows from the larvae of carpenter moths.

I was stunned. My usual methods were no help in this kind of environment. Along with a few C. pleuricapitata and O. macroacicularis, we also found Tilachlidiopsis nigra and Cordyceps takaomontana. It was a great yield, but it felt like I had been given the results, not that I had discovered them myself.

The host larvae of O. macroacicularis are large, growing up to seven or eight centimeters. Once the fruiting body is included, the total height often exceeds fifteen centimeters. Other species that parasitize the same host include Cordyceps indigotica and Cordyceps hepialidicola, though I did not manage to find them.

Ophiocordyceps macroacicularis

Ophiocordyceps macroacicularis is a large, needle-like species with exposed perithecia. Ascospores measure approximately 160–280 × 1.8–2 micrometers.

After returning home, I began searching the base of every knotweed plant I came across. I never found O. macroacicularis, but I did discover clusters of Ophiocordyceps nutans, which parasitizes stinkbugs, in similar environments. I have never been a fan of large group forays. I used to imagine them as chaotic events where everything gets picked clean. But I have to admit, they are an excellent way to learn.

The painting shown here was created shortly after I returned from that trip. It is based on the impressions that remained with me. In reality, the undergrowth was much denser, but just like in the picture, O. macroacicularis was rising from the base of Japanese knotweed.

In the Thicket, 2003. Tempera and oil on board. 33.4×21.2cm

Cordyceps tuberculata - November 2007

When autumn deepens and the wind starts to sting the skin, I begin to notice adult moths clinging to the riverside trees with rows of thin white spines protruding from their bodies.

There are many Cordyceps that grow from larvae or pupae, but those that grow from adult insects, especially in their sexual (teleomorphic) stage, are quite rare. Among them, the moth-associated group known as Cordyceps tuberculata is relatively common.

This particular moth fungus comes in many forms. Depending on the color and shape of its fruiting bodies, it might be called Cordyceps tuberculata, Cordyceps tuberculata f. flava, Cordyceps tuberculata f. moelleri, or referred to by other descriptive names like “brush-headed,” “grain-spined,” or “clustered” moth fungus. The asexual (anamorphic) stage is sometimes called Akanthomyces aculeatus or Akanthomyces pistillariiformis. Whether these forms are distinct species, developmental stages, or just individual variation remains unclear. It’s a confusing group.

Cordyceps tuberculata

Cordyceps tuberculata develops on the backs of adult moths, forming aerial, irregularly club-shaped fruiting bodies measuring 3 to 7 mm in height and 0.6 to 1.6 mm in diameter. Usually appearing singly or in clusters of up to seven, they are white with citron-yellow, elongated perithecia covering most of the surface. This species can be found year-round on tree branches, leaves, or cliff faces in mountain forests.

In the summer of 2005, I happened to find a fresh specimen of Cordyceps tuberculata f. moelleri and was able to observe its development for nearly a year. Here is what I recorded:

August 8, 2005: The first time I saw it, it looked like the moth was dusted with white mold. It wasn’t even clear yet whether it was a Cordyceps.

August 29, 2005: Several white spine-like structures had started to grow. It was beginning to look like a fungus.

September 27, 2005: Tiny yellowish fruiting bodies had formed, and it looked like it might already be mature.

February 11, 2006: No visible change. The fungus appeared to be overwintering. I started to wonder if it had withered away.

May 29, 2006: The spine-like structures had begun to swell in the middle, and new yellow fruiting bodies were forming.

June 19, 2006: Fully mature. After a while, the structure held its shape, but by the following month, it had disappeared.

Not every specimen follows this same pattern. Some may overwinter without fruiting and mature the following summer. Most are probably knocked off by wind and rain before they can reach that stage.

The painting shown here is from my “Fungus Age” series. It depicts a scene from a time when Cordyceps infections had begun to spread among humans. Eventually, humanity vanishes and the age of fungi takes over.

The species shown in the painting is in its asexual form. Even without the fruiting bodies, this is considered its mature stage. Adult moth-associated anamorphic fungi like Akanthomyces aculeatus and Akanthomyces pistillariiformis are difficult to tell apart by appearance alone.

Treatment, 2005. Tempera and oil on board. 22.7×15.8cm

Cordyceps capitata, Cordyceps canadensis - January 2008

When people think of Cordyceps, they usually imagine fungi that parasitize insects or spiders. But there are a few unusual types that actually grow from other fungi. These are known as fungicolous Cordyceps, and they typically infect underground fungi like Elaphomyces and Rhizopogon species.

Among these, Cordyceps capitata, Cordyceps canadensis, and Cordyceps ophioglossoides are common and widely distributed around the world. They are relatively large for Cordyceps fungi and sometimes get picked up during mushroom hunts. In the forest behind K Temple, where I often explore, I can find dozens to over a hundred C. capitata and C. canadensis emerging in spring. Even in the middle of winter, if I carefully search beneath the leaf litter in areas where they typically appear, I can often find small, bean-shaped greenish heads just poking through the surface. These are the immature fruiting bodies of Cordyceps, lying dormant through the winter and rapidly growing once spring arrives.

Cordyceps capitata

Cordyceps capitata and Cordyceps canadensis parasitize underground fungi such as Elaphomyces. The fruiting body grows upright from the host, with the head forming at the tip of a slender stalk. C. canadensis is typically smaller, darker, and has a noticeably slimy texture, while C. capitata tends to show more variation in host preference.

These two species are not only similar in appearance but also share nearly identical habitats, making them hard to tell apart. In the field near K Temple, they grow mixed together, and at first I thought they were all C. canadensis. C. canadensis, as its name suggests, is somewhat slimy, but C. capitata can also appear slick when wet with rain or dew. The former tends to have a darker head and a yellowish stalk, but the variations within each species make this unreliable. Under a microscope, their spores differ significantly, which makes identification easy. Even without magnification, slicing a fruiting body lengthwise reveals a clear distinction—C. capitata has a pure white interior, while C. canadensis is yellowish and semi-translucent. That said, there are many other fungicolous Cordyceps species, so caution is always advised.

Cordyceps capitata

Cordyceps capitata and Cordyceps canadensis typically appear from summer to autumn, but in western Japan and farther south, they can also emerge during winter. C. capitata is often found in beech forests and sometimes in pine forests as well.

In 2007, a major revision of Cordyceps taxonomy was published. Many fungicolous species, along with others like Cordyceps takaomontana and Cordyceps rosea, were moved into a newly created genus, Elaphocordyceps. As such, Cordyceps capitata and Cordyceps canadensis are now classified as Elaphocordyceps capitata and Elaphocordyceps canadensis. However, since these new names have yet to gain wide acceptance, I’ll continue using the older names for now. I should also mention that some species I’ve previously introduced have since been moved to Ophiocordyceps.

The painting here is part of a series themed around “sweets.” This piece features truffle chocolates, with C. capitata coated in chocolate. Unlike real truffles, however, the Elaphomyces hosts of these fungi are not edible. And to date, no Cordyceps species has ever been found growing from an actual truffle.

Just to clarify, truffle chocolates are named for their shape, not because they contain real truffles.

Making Truffle Chocolates, 2007. Tempera and oil on board. 33.4×21.2cm

Hymenostilbe odonatae - March 2008

Hymenostilbe odonatae is not as well-known as Cordyceps sobolifera or Cordyceps militaris, but among those who know something about Cordyceps, it is one of the most admired species. It infects large adult dragonflies and damselflies, and its dramatic appearance likely contributes to its popularity. From the segments of the host’s body, it produces multiple pink, horn-like projections, creating an almost extravagant display.

This is the fungus in its asexual stage. Its sexual form, known as Ophiocordyceps odonatae, is extremely rare.

Hymenostilbe odonatae

Hymenostilbe odonatae (anamorphic stage) parasitizes the body segments of dragonflies. It is an aerial species with irregular, distorted fruiting bodies that measure 2.5 to 10 mm in height and 0.5 to 3 mm in diameter. The color is pale salmon pink, with lighter or white tips. Conidial spores form on the upper portion.

I became interested in Cordyceps about seventeen or eighteen years ago. Back then, even finding a standard Hymenostilbe odonatae was considered so rare that it could make the newspaper. I hoped to encounter one someday, but I never imagined that I would find it in the satoyama forest near my own studio.

After nearly ten years of solitary and mostly fruitless searching, I joined a Cordyceps research group. The senior members of the group were well-informed and told me that Hymenostilbe odonatae was not actually rare and could be found in nearby lowland forests.

Encouraged by this, I decided to go out one day in May, a little early in the season, to search along the K River. I did not even bring rubber boots, so I carefully moved along the riverside slope, trying to stay dry. At some point, a flash of pink caught my eye on the ground. I bent down and picked it up without much thought. It was a tiny rod, about two centimeters long, painted in alternating black and white stripes, with little pink horn-like growths on it. It took me a moment to realize I was holding the broken tail of a dragonfly from which the fungus had sprouted. I immediately searched the surrounding ground and tree branches, hoping to find the rest of the body, but it was nowhere to be seen.

The next year, I finally found a complete specimen. In April, I spotted one growing from a red dragonfly, and in June, I found a larger specimen growing from a bigger dragonfly species. It seemed that what I had been told was true—this fungus was not all that rare.

Hymenostilbe odonatae

Hymenostilbe odonatae occurs in humid environments such as riverbanks, wetlands, near waterfalls, on tree branches, bamboo stems, and fallen logs. Found in Japan and New Guinea, it can be observed year-round and sometimes appears in cyclical mass emergences.

The large specimen was especially striking. I placed it in a display case and showed it alongside a dragonfly-themed painting at an exhibition. One visitor was so interested that they offered to buy the painting if I included the specimen. I agreed and sold them together. I assumed I would find another one soon.

Perhaps that was wishful thinking. After that sale, I could not find another specimen at all. It felt like a curse. Seven years passed before it finally began to lift. Last year, I encountered two dragonfly fungi again, although only one was actually found by me. I wonder if I will find one this year.

The painting shown here was made the year I found my first specimen, although at the time I had not yet seen a fully intact one. The piece that was sold with the artwork was not the one shown here. The term “follow-up cultivation” refers to collecting an immature specimen in the wild and allowing it to mature at home.

Subculturing, 1999. Tempera and oil on board. 27.3×16cm