Utopian Polis and the Ruins of Space-Time

Zhao Xiaodan (Curator)

2025

We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.

— from Little Gidding, Four Quartets, T. S. Eliot

I. The Thrown World and Sensory Archetypes

Shigeo Otake was born in 1955 in Kobe, Japan, into a traditional Christian household. His artistic practice has been deeply influenced by his family background, the cultural conditions of postwar Japan, and the nostalgic and grotesque sensibilities of the Shōwa era. Kobe lies between Mount Rokko and the Seto Inland Sea, a natural port city shaped by gradual ecological strata. This environment nurtured his childhood experiences of coexistence with nature, a perceptual engagement with insects and marine creatures, and a strong imaginative connection. Otake showed a precocious talent for drawing and imagination from an early age. Before entering Kyoto City University of Arts, he spent most of his formative years in Kobe. In a world into which the self is cast, childhood experience often continues to shape the architecture of the inner life through the unconscious. Otake’s upbringing in Kobe gave him early exposure to nature, religious practice, and esoteric knowledge, all of which became latent archetypes for the subtle and specific visual worlds he would later construct.

The Demon at the Top of 50 Steps, 2022

. Tempera and oil on board.

27.3×19cm

A 50-step staircase in Kobe where the artist spent time during his childhood. Courtesy of the artist.

Beyond this natural extension of personal experience, Otake’s artistic development also unfolded within the framework of late twentieth-century intellectual exchange between Japan and Europe, particularly Italy. From the 1970s, Japanese intellectual and cultural circles became increasingly attentive to European postwar reflections on modernity. The metaphysical paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s cinematic narratives of the sacred and the corporeal, and critiques of functionalist aesthetics in architecture and design exerted a profound influence on Japan, which itself was processing the psychological sediments of a post-ruin era. In 1974, Otake entered Kyoto City University of Arts during a time when Italian thought flourished on campus. Under the guidance of Koji Yamazoe, he systematically studied fresco and egg tempera painting during his first two years. This return to traditional image-making reflected his sensitivity to the ruptures of modernity. Soon after, he took a leave from school to begin a journey across Europe, almost in the spirit of pilgrimage. He visited many of the continent’s key religious sanctuaries and art museums and encountered firsthand fragments of Northern European history. This two-year journey laid a spatial foundation for his artistic practice and deepened his spiritual connection to the sacred image.

A map provided by Shigeo Otake, documenting his travels in Europe during the 1970s.

After this grand tour, Otake did not stop pursuing the traces of human civilization mapped across the globe. Whether led by the search for holy relics or by other drives, during the 1980s he traveled to China, Egypt, Israel, and several countries in Eastern Europe including Romania, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. This decade of intense travel was his deliberate attempt to link his body and consciousness to the remnants and landscapes of civilizations. The impressions of these journeys resurfaced continually in his later works, many of them reimagined as the habitats of the “residents” within his paintings. These figures were first rooted in his study of exceptional organisms in nature, insects, marine species, and after 1985, fungi. These spiritually charged creatures appear in his paintings in various forms of disguise, performance, and succession. Through a mimetic mode of thinking, they enact almost complete life histories within the painting’s space.

Notably, despite encountering numerous ruins during his travels, depictions of such sites were rare in his early works. Much like his first encounter with the tall Lepiota mushroom, which led to a three-year study of fungi before they appeared in his paintings, ruins too entered his pictorial universe only after a period of delay. This reflects an extremely rigorous form of curatorial judgment within Otake’s artistic world. The early residents in his work each possess survival, predatory, or reproductive capacities that exceed conventional human comprehension. His stringent selection and careful placement of these creatures within his visual compositions imply a deep awareness of ethical order in pictorial space. Through this process of visual ethics, Otake assumes the role of a scholar, granting these beings the right and legitimacy to exist within the image. Through metaphor, they gradually infiltrate the cultural field and secure their place within it.

Herodium archaeological site, Bethlehem, Israel, 1985. Courtesy of the artist.

II. From the Hanshin Earthquake to the Ruin of Consciousness

The sense of time slowed, life transformed, and the orderly yet flourishing spatial structures were all evident in Otake’s works created before 1995. Had there been no external cataclysm, the ideal city-state depicted in his art might have remained forever lodged in fortresses, towns, and churches of European classicism, or in the nostalgic ambiance of Japan’s Shōwa era, exuding an amber-like density, warmth, and constant glow. In the early morning hours of January 17, 1995, a major earthquake struck the Hanshin region. It was the most devastating natural disaster Japan had experienced since the war. The quake not only destroyed the geographical landscapes of Otake’s childhood and youth but also shook the carefully cultivated order and ideals he had embedded in his paintings. In an instant, his homeland was reduced to rubble. The rupture of physical space triggered a profound rift within his spiritual world. A massive invisible emergence, what Timothy Morton refers to as a “hyperobject,” pressed in with overwhelming force on the bodies, emotions, and imaginations of those affected, attaching itself like a ghost to space, language, and even behavior. It was in the wake of this disaster that the spatial structure of Otake’s work underwent a marked shift. Ruins no longer appeared as distant remnants of civilization. They became an immediate structural reality that forced a reorientation of vision and prompted repeated recompositions and returns between memory and image.

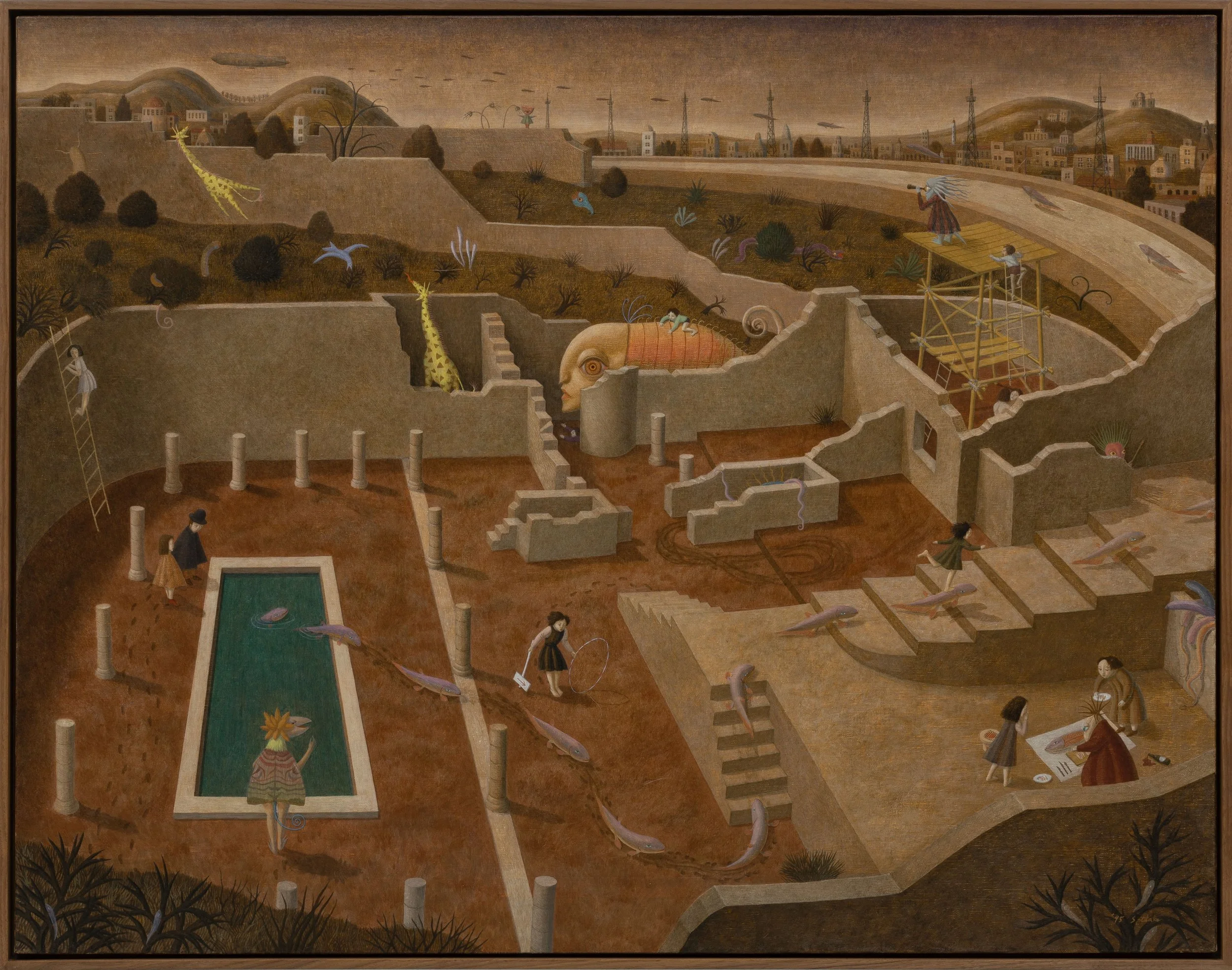

Contented Place, 1991. Tempera and Oil on canvas. 91×116.7cm

Consider the works Contented Place (1991) and Lungfish of the Ruins (1995) as examples. Though created four years apart, the two paintings mirror each other in their spatial choices. Both refer to Herodium, a site Otake visited in 1985 near Bethlehem in Israel. Contented Place portrays a restored Herodium, its residents immersed in the sanctity and spiritual aura of a once-great architectural marvel. The tranquil and harmonious atmosphere of the scene also reflects the hedonistic sensibility of the Shōwa era. By contrast, Lungfish of the Ruins, painted after the earthquake, ruptures the ideal order previously woven into his vision of utopia. The lungfish, a species Otake had encountered during his travels in Egypt and known for its ability to survive drought by hibernating until the rainy season, becomes a symbolic vehicle of transition in the painting. The fish’s migratory path transforms into an airship, visualizing Otake’s will while also suggesting that ruins contain within them the possibility of continuation and regeneration.

Lungfish in Ruins, 1995. Tempera and Oil on canvas. 90.9×116.7cm

Peering beyond the surface of real ruins, Otake’s gaze toward history, life, and memory transforms the ruined landscape into an ontological vessel. As Walter Benjamin described in The Origin of German Tragic Drama, ruins can function as allegorical and interrupted forms. They are not just rhetorical figures of civilization but extensions of historical consciousness. On this basis, Otake’s paintings began to engage more deeply with questions of order, faith, pain, and redemption. In 2012, he created Restricted Area, responding to the uninhabitable zone formed after the Fukushima earthquake and nuclear disaster the previous year. Although the composition is lush and vibrant, it sharply contrasts with the reality it represents. Radiation-induced desolation, mutation, and death are inscribed within the work, guiding Otake’s meditative gaze on spaces that cannot be approached. The space formed in Restricted Area transcends the actual ruins, becoming an allegorical landscape. It constructs a modern version of a place like Contented Place, now impossible to return to. At the same time, it signifies the symbolic aftermath of technological collapse and expresses a longing for reconstruction and salvation in a post-apocalyptic world.

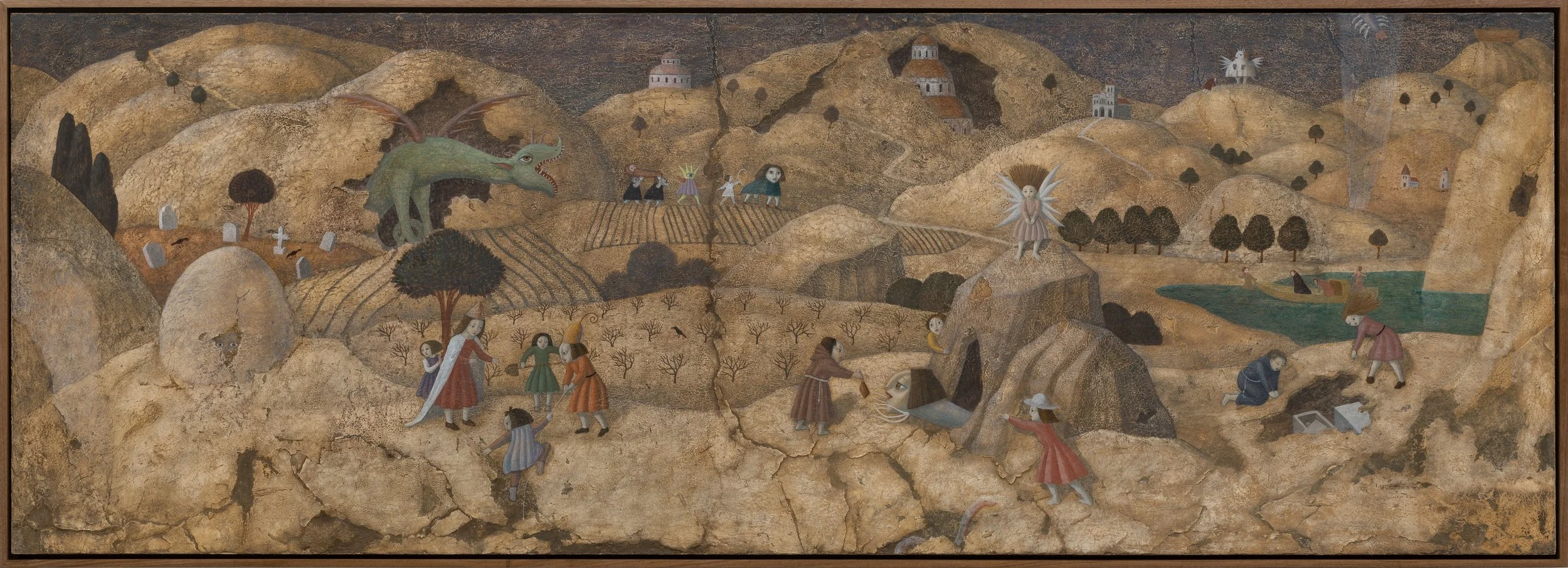

Restricted Area, 2013. Tempera and Oil on board. 40.9×53cm

From cities shaped by optimistic visions to reflections and rebuilding among collapsed fortresses, ruins for Otake ceased to signify the end of physical space and instead became entry points into a ruinous state of consciousness. The personal trauma of the Hanshin earthquake gradually evolved into a pointed critique of the logic of modernity. Also painted in 1995, Blind Alley pushes the semantics of ruin into the philosophical realm. Inspired by a circular plaza in Lucca, Italy, the artist deliberately transformed its open structure into a closed spiral. The spiral, often a symbol of life’s cycles, return, and introspection, resonates with Otake’s continued interest in the hard and ancient shells of marine creatures. However, the title Blind Alley negates the symbolic optimism of the spiral, suggesting instead rupture, stagnation, even a sense of dead end. This stands in striking contrast to his 1992 monumental fourteen-meter mural Transformation of the City, which unfolds like an earthly paradise. That work evokes the imagery of Venetian canals and reveals the artist’s ambition to construct a Bosch-like grand narrative. Blind Alley, as a post-earthquake self-denial, encloses its pictorial space yet radiates a claustrophobic pressure from within. It becomes an image not only of blocked spiritual pathways but also the breakdown of linear perception itself.

Blind Alley, 1995. Tempera and Oil on canvas. 130.3×162.1cm

III. A Pact with the Ruins

Unlike the 18th and 19th century European aristocrats who sought a stylized sense of the sublime within ruins and incorporated that aesthetic into their landscaped gardens as part of romanticist ideals, for Shigeo Otake, ruins were never decorative relics of the past. Rather, they were sites where sensory fissures occurred. In these fractured spaces, time dislocates, meaning unravels, and wreckage becomes spiritual vessels coexisting with history. These ruins may appear silent, yet they are charged with tension. The impact they provoke goes beyond sensory oppression. They provoke a profound inquiry into the nature of time itself and the depths of the spirit. The ruptured paths and collapsed spaces that Otake presents in his work are not merely physical demolitions. They symbolize the collapse of the meaning structures he constructs in painting as they collide with the weight of reality. In this context, Alois Riegl’s concept of “age value” in historical relics becomes a visual reality. The erosion of time leaves visible traces on surfaces, bearing events and memories that resonate emotionally with viewers. For the artist, these traces become the starting point for a new aesthetic.

Otake’s 1996 work Heritage is a direct embodiment of this idea. The foundation of the piece is a century-old wall from the artist’s ancestral home, severely damaged in the earthquake. Using fresco transfer techniques, Otake salvaged it from destruction. Instead of concealing the wall’s fractures, he followed the irregular trajectory of these cracks to develop the composition. The imagery in the painting draws from the Golden Legend and its stories of saints, yet it also incorporates local narratives that unfolded on the very wall itself. The work interweaves post-earthquake ruins with civilizational remnants, evoking places toppled by sudden forces and reflecting the artist’s contemplation of whether such forces are natural disasters or divine punishment. Ruins here become a field for exploring the rupture and repair of history, the symbiosis between humans and multiple species, and the interdependence of civilization and nature. These spaces, in a sense, mark the potential arrival of a new sacredness. As Georges Bataille elevated ruins to the extreme of the sublime, so too might this new sacredness sprout from below, from decay, rot, and disintegration, revealing what he described as a “divinity of the low.”

Heritage, 1996. Tempera and oil on board. 63×180cm

Ruins are viewed as grounds for the renewal of life’s pacts. In a scene where overall meaning has disintegrated, redemption appears like a lightning flash of modernity, emerging from the fracture and chaos. The crumbling walls and the roar of reality made Otake realize that perhaps, at the junction where ruins and time meet, there might lie the still-unrealized radiance of the messianic. Heritage presents a hybrid structure. The artist clusters layers of life’s perceptions upon a fractured surface and continues to apply this method of assemblage in his later works. By this time, a decade had passed since his first encounter with fungi. From mushrooms of various shapes to Cordyceps parasitizing insects, his search for and identification of rare species honed his eye into that of a highly efficient and sensitive tracker. In his later creations, overlapping and interwoven motifs become increasingly prominent. These motifs are laden with signals and connect disparate worlds and dimensions. The entanglement and symbiosis of fungi and city ruins, subterranean tunnels and subways transforming into waterfronts and fortresses, museums, aquariums, and planetariums turning into sanctuaries for hidden species, all these excavations of heterogeneous spaces gradually form a vast and transgressive spatial network.

Waterfront,

1990.

Tempera and Oil on canvas.

45.5×53cm

An abandoned JR railway tunnel in Kobe. Courtesy of the artist.

IV. Symbiosis and Coexistence in Multispecies and Heterogeneous Spaces

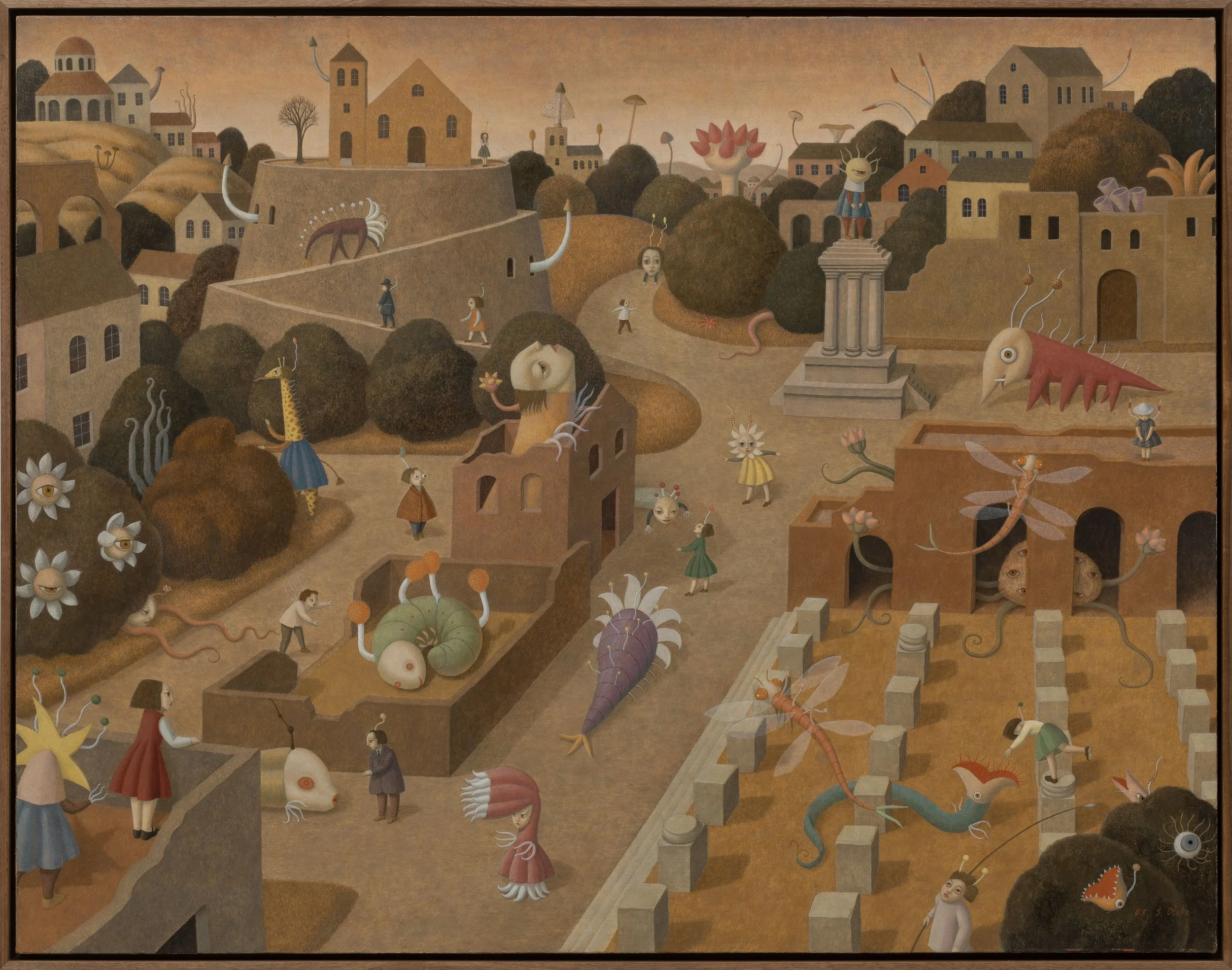

In the visual structures crafted by the artist, humanity never occupies the central position. Guided by figures such as Virgil and Beatrice from Dante’s Divine Comedy, or characters like Alice and Little Red Riding Hood, Shigeo Otake’s paintings present minute apertures through which one may traverse a labyrinth of vision. The nostalgic hues and heterogeneous motifs in his works are manifestations of the spirits of small beings concealed beneath the landscapes of reality. In this process, humans become observers, witnesses, and eventually cohabitants in symbiosis with a multitude of life forms.

One representative example is the painting Vegetable Garden (2006), which is set at Otake’s studio in Nagaokakyo, Kyoto Prefecture, where he lived for over forty years and which served as the starting point for countless excursions into the nearby mountains. Surrounded by rice fields and vegetable plots, the studio is vividly depicted on canvas and not only embodies the artist’s painterly methodology but also exemplifies the nearly perfect transformational logic present in his visual language. The guides from earlier works are now transformed into figures peering out from windows onto outdoor scenes, emphasizing a latent sense of danger lurking in the surroundings. This sense of threat arises from the sudden metamorphoses of animals and plants outside.

Vegetable Garden, 2006. Tempera and Oil on board. 90.9×116.7cm

The artist’s meticulous brushwork is not merely a stylistic choice but a method for conveying and enacting various modes of relationship with non-human life forms. As demonstrated in the narrative cycle Mycological Age (2005–2008), Otake explores scenarios of real coexistence between humans and fungi. In his narrative, fungi appear like wandering Bohemians who intrude upon human settlements, infect local species, and trigger the partial collapse of civilization. Through a certain “substrate,” humans and other species connect and coexist with fungi, evolving into a new type of human being. This scenario is captured in Human Memorial Park (2008), which depicts these newly evolved humans looking back upon the physical spaces once inhabited by the old human race. As in many historical moments, such sentiments of nostalgia invariably arise. The coexistence of fungi and humanity in Otake’s works not only presages the COVID-19 pandemic over a decade in advance but also echoes the earlier SARS outbreak in China and Southeast Asia. At present, we are living within such a collective memory.

Human Memorial Park, 2008. Tempera and oil on board. 90.9×116.7cm

The world Otake explores grows from landscapes where fungi thrive, from mountains and gardens, as well as from habitats shared by marine and terrestrial species. Within the decay and fragmentation of life, these species construct a subtle ecological order that coalesces into the ecological ethics of his paintings. Through theological frameworks, the artist introduces a form of non-transcendent redemption that does not seek to restore a primordial order but rather to interlink with the world of minute organisms and to coexist with sticky life forms. Within the spiritual space inhabited by dust, debris, and mold, he invites us to perceive a kind of “theology of descent.” The life forms depicted in Otake’s paintings are not limited to microscopic communities in nature but increasingly evolve as parallel metaphors for the human condition. Just as hermit crabs gather to exchange for more suitable shells as they grow, many life forms across the sea, land, and air practice survival strategies such as borrowing, cohabiting, or parasitizing. These species enact survival through continual borrowing, replacing, and adapting, thus forming an elastic state of existence without the need for permanent belonging.

The subtle and dynamic survival strategies of these life forms offer more than phenomenological insights into natural ecology. For the artist, they metaphorically address humanity’s attachment to the idea of dwelling and the lifestyles built upon it. In the socio-economic aftermath of Japan’s burst bubble economy, once-stable structures such as family, institutions, and architecture became hollowed out like abandoned shells and faced the instantaneous dissolution of their overlying values and meanings. Otake’s The Night of the Great Tide (1999) and Resort (2001) reflect such a condition through mimetic hermit crabs and multispecies entities, offering a direct visual feedback on human existence under the economic strain of the time. Similarly, Grylli Day (2008) expresses a vision steeped in catastrophe. Using the biblical image of locusts as harbingers of judgment and warning, Otake presents an apocalyptic tableau of ecological disorder and disaster. The locusts’ rampage signifies not only environmental devastation and resource plunder but also the collapse of social systems and the inevitable self-exile of humanity. His paintings are imbued with critical force. Notably, Otake does not turn to a conventional eschatology. Instead, within the fissures of crisis, he continuously reveals the potential for a non-transcendent redemption.

Night of the Great Tide, 1999. Tempera and Oil on board. 27.3×40.9cm

What ultimately prompted Otake to expand his meditation on redemption from micro-ecological relations to allegories of human nature was a harrowing event in his hometown: the 1997 Kobe child murder case involving the perpetrator known as Sakakibara Seito. The perpetrator’s age, murky motivations, and the ambivalent public reaction led Otake to recognize that evil does not always erupt abruptly but often lurks within the interstices of daily ethics and institutional structures. From that point forward, he began to scrutinize those boundaries that appear stable yet are constantly shifting, the gray areas between individual and environment, responsibility and growth, discipline and abandonment. The “Juvenile Classification Center” as a real-world institution began to recur in his paintings, both as a ruinous structure and as a metaphorical representation of the mechanisms by which humanity categorizes and expels. The artist keenly perceived how such spaces exemplify the classificatory impulse that modern society uses to delineate what counts as human. Each act of boundary-drawing not only delineates order but also generates new margins and castaways. His art thus becomes a visual invocation of these banished entities.

Juvenile Classification Center in Kobe. Courtesy of the artist.

Marine Meteorological Observatory in Kobe. Courtesy of the artist.

Beyond the “Juvenile Classification Center,” the “Marine Meteorological Observatory,” destroyed by the Hanshin earthquake, also appears repeatedly in Otake’s work. This structure symbolizes both humanity’s ambition to control nature and the inescapable, enduring coexistence between human understanding and catastrophe. At this point, the chimeric metaphors of disaster intersect with the mimetic structures in his paintings. Those composite forms assembled from ruins, biological entities, and architectural fragments from memory preserve a hybrid tension in shape and conjure apocalyptic imagery reminiscent of the Book of Revelation. This post-disaster mimetic language has not faded with time but has been reactivated at various junctures. When the COVID-19 pandemic broke out globally in 2019, Otake brought to an end his forty-plus years of life and creation in the outskirts of Kyoto and returned to his hometown of Kobe. This return marked not just a geographical relocation but also a spiritual homecoming.

The Last Days of the Mobile Fungi Garden, 1993. Tempera and oil on board. 53×72.7cm. Set in the abandoned JR railway tunnel in Kobe, this work features the phrases “Juvenile Classification Center” and “Marine Meteorological Observatory” subtly positioned in the upper left and upper right corners of the composition.

V. The Return to Kobe and the Unending Reflection

The artist’s exploratory journey and the hunter’s gaze he honed in the mountains and wilds did not lose their vitality in Kobe’s post-earthquake ecology. Instead, they transformed into a spiritually charged pursuit rich with symbolism. In the eyes of one who has returned home, the artist seeks to peel back the layers of complexity that lie hidden in this place. The buildings once toppled by the quake and the landmarks gradually lost to time have become vital coordinates in his efforts to trace history and recover memory. For Otake, Kobe is not merely a city in the literal sense. It is a composite of heterotopic spaces formed in the tension between rupture and rebirth, dense with fragments of history, emotional echoes, and personal recollections. His most recent works aim precisely to reveal the heterogeneous nature of such spaces. In Behind the Ijinkan (2024), which references the Kitano district of Kobe, former historical landmarks become silent yet psychologically charged vessels in his paintings. The Ijinkan, originally a settlement of foreign residents from the Meiji period onward, once bore the complex traces of exoticism, power relations, and displaced identities. Today, it has become a destination for sightseeing, though its layered past still lingers.

Behind the Ijinkan,

2024

. Tempera and Oil on board.

19×27.3cm

Ijinkan in Kobe.

Courtesy of the artist.

Beyond publicly legible spaces, the alleys of his childhood and places where he once paused and imagined now overlap and converge, generating a surging yet secret internal force. The Demon on the Fifty Steps (2022) points to a playground from his youth, near the Christian elementary school where he first received his education. Surely the Demon’s House (2025) and The House Full of Windows (2025) reflect the artist’s curiosity about and imagination of the inner possibilities of enclosed and open spaces. Much like Julio Cortázar’s description of an unknown presence in Casa Tomada, that unnamed force and the anxiety it brings to space are given a more intimate and enduring form in Otake’s work. Moving between collective memory and private domains, these images do not depict static spaces but rather serve as portals through which psychological fissures and symbolic redemption are released.

The House Full of Windows,

2025

. Acrylic on paper.

24×27cm

A house in Kobe. Courtesy of the artist.

In Crossroads of the Six Realms (2024), the dislocated streets, elongated shadows, the child’s dice, and the roulette wheel in the background all speak to questions of reincarnation and chance within both physics and theology. The question “Does God play dice?” and the six-realm wheel of samsara are here woven into a riddle waiting to be solved. The elongated shadows and spatial distortions may also resonate with Giorgio de Chirico’s deserted squares and his Nietzschean reflections on postwar existential crisis. As Nietzsche wrote, “The shadow lengthens because the sun is setting,” a metaphor for the latent unease and nihilism lurking in the twilight of civilization. In Otake’s visual language, such spatial treatments awaken viewers to reflections on the state of human existence and express the trauma of post-disaster urban experience. Kobe for Otake is what Turin was for de Chirico, a birthplace of spiritual and obscure visions.

The Crossroads of the Six Realms, 2024. Tempera and Oil on board. 22×27.3cm

To coexist with all that remains unspoken and mysterious, the artist invites us to look from the depths of time and space into the interwoven threads of history and civilization, species and ecology, theology and reason. Like a hermit or a medieval scribe, Otake silently releases endless imaginings into the margins of the page. Through delicate brushwork and symbolic structure, he persistently penetrates the surface of things, reaching into the essence and foundation of existence. He weaves together perceptual images that nest within one another and mirror each other. His painting responds to the question of how we inhabit an alienated world and seek spiritual redemption amid rupture and disorder. In this inwardly expansive space, the artist constructs an entirely new coordinate system. Within it resonates his profound gaze into the realm of suffering and his continuous inquiry into how we might dwell within it.